by Stephen M. Priest, MMR/photos by the author

by Stephen M. Priest, MMR/photos by the author

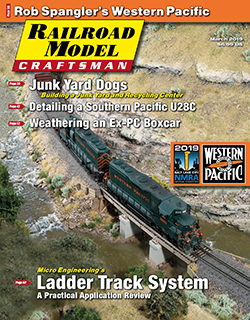

The thought of building the huge Chesterfield Yard on my HO scale proto-freelanced Santa Fe St. Louis Division was daunting. The sheer number of turnouts needed and the looming deadline of the NMRA 2018 National Convention in Kansas City weighed heavily on my time and challenged my energy level. I had planned on hand-laying the yard leads, but as the deadline loomed, I began to look for alternatives, including having others lay the yard leads for me.

Out of the blue, while searching for something entirely off-topic, I stumbled across the Ladder Track System manufactured by Micro-Engineering. First, I must tell you that I am a fan of Micro-Engineering and have purchased, built, and enjoyed their products for years. For some reason, however, I totally missed the introduction of the Yard Ladder System, possibly because I did not have a need for it in the past (I also have become a fan of hand-laying track). Having worked with Micro-Engineering in the past, I called my friend Ron, the owner, and picked his brain about the system, what made it unique, and how it worked. Having been a former Assistant Manager of Track Geometry system-wide for the Santa Fe and later BNSF, I could talk track. I am very impressed with Ron’s yard lead system. We talked track for most of an hour, and I came away from the conversation having placed a large order for track and the turnouts needed to lay the entire Chesterfield Yard.

Templates Galore

Ron also sent me some PDF files (available on Micro-Engineering’s website) that can be printed and used as design templates, making planning quick and rather painless. I printed dozens of the templates out on heavy paper and called my good friend Keith Robinson over to work with me as I brainstormed and laid out the huge yard. After about an hour of talking and scheming, we decided that the yard should be broken down into two separate yards: a joint receiving and departure yard and a classification yard. These two yards, organized in a serial arrangement, both serve important — but different — tasks, each needed to make up and break down trains at Chesterfield. By placing the two yards end-to-end and managing their overall width, all tracks are kept within reach of the operator, making his or her task of switching easier and far more enjoyable.

The Cycle

The receiving and departure yard in-bounds trains, and the power and waycars are pulled off the train and hostled to their appropriate facilities for servicing. Meanwhile, the cut of cars that was the train is pulled to the classification yard where it is switched. The process of switching mainly consists of placing cars going to similar terminals together, forming a new train. Sometimes cars are in blocks when they arrive at the yard, and sometimes they are singles, meaning that each and every car must be switched to a track with other cars going to a similar destination.

Once a track in the classification yard is full, the cars in that track are then moved back to the receiving and departure yard where motive power from the Diesel Service Facility and a recently serviced and cleaned waycar are added to the cut, making it a train. The paperwork is then checked, and the train is walked to make sure all the cars are in order and match the car cards. A crew can then be called to take the train out of Chesterfield and onto its destination. On the prototype railroads, the arrival and departure yards are often — but not always — separate. Because of available space (or lack thereof), it makes sense to combine those two yards and their functions. There is prototypical precedence for combining the two.

Good yard design must consider the length of the yard tracks, comparing them with each other and the available lengths of sidings on the layout. You don’t want the ability to create trains that will be too large to fit in your available sidings. Conversely, you do not want yard tracks that are so short you have to double-over every arriving and departing train to yard the trains. Balance and a bit of standardization is the key.

My entire layout was designed with the standard measuring “stick” of 30-car length trains. Those 30-car lengths are 50-foot as a design standard, and the trains we build in our yard and the train length limit placed on locals picking up cars from industries is 25-car lengths. Yes, several sidings are considerably longer than 30-car lengths, but none shorter. The dispatcher can give trains permission to operate over tonnage, but these trains will have to be doubled-over once they reach Chesterfield Yard. The overarching goal is to keep this activity to a minimum.

Now that we had our main yard design established, we looked at our traffic patterns to tweak our design so that it matched the operating scheme. Since Chesterfield Yard is in St. Louis, we knew we were going to be running transfers to and from the Santa Fe to Norfolk & Western, Southern, Conrail, Louisville & Nashville, and other roads. These transfers originate in the staging yards and are inbounded and outbounded the same as other trains, except the Santa Fe at Chesterfield would not service their motive power and waycars.

During switching operations, we periodically needed a place to slough power and waycars blocking work. At the same time, we needed a place to store and service our waycars and tie up our switch engines and local power. Our design response was to locate a pair of long tracks between the R&D and classification yards, paralleling the yard leads. This location is ideal for quick access to the waycars and is double-ended, potentially allowing two jobs to access the tracks at once. This design addition also provides a centralized point to stash anything the yard jobs need to get “out of the way.”

Yard Lead Bypass Tracks

We designed bypass tracks into the yard plan to keep inbound and outbound trains from having to pull their trains down the switch leads and over all the turnouts. Trains operating in and out of the yard can do so independently, leaving the yard leads to the switch engines working there. Being able to do anything simultaneously in a yard on your layout is a huge advantage because most operational bottlenecks occur in yards. Leaving your yard engines free to work while mainline trains arrive and depart is an attractive concept that keeps the yard car dwell time to a minimum.

The “System”

So far, I have talked about design criteria and the needs of the layout with the yard as the specific focus. I want to take some time explaining the Ladder Track System and why it is so revolutionary. Yard trackwork and the ability to maximize the amount of track within a small space is key because you have to reach the cars to switch. Although it would seem like a great idea to have a 30-track-wide bowl to classify your trains, this is nearly impossible in model form because the average comfortable human reach is around 30-inches. This reach limitation forces us to design accessible yards with a narrow width.

Your chosen scale to model will also have some limitations as well, with N scale being able to support a higher number of tracks than O scale will. In HO scale, you can get 10 to 12 tracks with easy access and up to 20 tracks with limited access to the last 5 or 6 tracks. Magnetic couplers and uncoupling magnets can help but can also introduce challenges, including accidental uncoupling of cars if any slack occurs when the cars are being pulled over the magnet. We decided early on that we wanted easy access to all the yard tracks, and since our yard is accessible only from one side (the aisle), we limited our tracks to 11, counting the double-track main line that runs behind the yard.

The Ladder Track System is designed to provide up to 30 percent more usable track length in the same yard space when compared to common generic turnouts. The system is made up of No. 5 turnouts with geometries that achieve a far more compact yard. Combined with curved diverging tracks, increased ladder track angles, overlapping turnouts, and shorter turnouts, the system really goes to work for you, increasing yard capacity. The NMRA specifies that the minimum spacing between track should be no less than 2-1/16th of an inch. This system is designed around those numbers, and we have had no issues operating with that track spacing. Of course, the amount of additional space actually gained in your yard will depend on how large your yard is and what type of configuration your yard takes. Obviously, the larger your yard, the more car capacity is gained.

Initially, as I was reading about this new yard-specific track system, one of my concerns was the operation of 89-foot cars. I am old enough and smart enough to know that you don’t get something for nothing, and a tighter yard arrangement could create problems for longer cars. Before adopting the system, I tested the operations of several common 89-foot cars by mocking up a lead, pulling and shoving cars through the trackwork. I even tried some rather nasty-looking double S-curve designs, hoping to discover the limits of the track system. To my surprise, the trackwork performed well right out of the box! The cars stayed on the track even when being shoved at an aggressive and somewhat unrealistic pace. I was sold!

Pieces and Parts

The Ladder Track System includes five different and specific turnouts, each with a designed purpose. Three of the turnouts have a fairly conventional look, but two of the five are like nothing you have ever seen, and it is those two pieces that really make the system pioneering. Micro-Engineering labels the five turnouts: No. 5a, No. 5b, No. 5c, No. 5d, and No. 5e. This simple labeling system is easy to remember and provides a flexible approach to your yard ladders. Here is a brief overview of the components:

No. 5a Standard Turnout

This turnout is a standard No. 5 turnout with an 11.42-degree frog angle and a straight Diverging Track. The Point End of the turnout has an additional four ties, making it slightly longer than a normal turnout.

The additional four ties allow connecting a series of No. 5A Standard Turnouts, one after the other, to form a ladder track where each body track, including between the main line and the first body track, has 2-1/16 inch track spacing (the NMRA standard). The angle of the ladder track will be the same as the frog angle: 11.42 degrees. A ladder track made using No. 5a’s forms a “classic” yard often seen in large, prototype yards but is not a space-saving type of ladder track.

When the No. 5a Standard Turnout is used for other than a ladder track, the additional ties on the Point End can be left straight, flexed to a curve or trimmed off, as desired.

No. 5b Curved Diverging Track

This turnout is different from a standard No. 5 turnout in that it has a curved Diverging Track and without the additional four ties at the Point End of the turnout.

For space-saving yards, the No. 5b Curved Diverging Track turnout is the turnout used most often as the first turnout of a ladder track, coming off the main line. This is because the curved Diverging Track effectively increases the ladder track angle from 11.4-degrees of a standard No. 5 to 16.2-degrees, which allows longer body tracks for the same layout space.

Connecting a series of No. 5b Curved Diverging Track turnouts — of the same hand — easily forms a pinwheel yard.

The No. 5b Curved Diverging Track turnout can be used anywhere a larger Diverging Track angle is needed.

No. 5c Lead Ladder

This turnout is a shortened turnout, ending just past the frog and guard rails at the Frog End of the turnout. The ends of the Through Track and the Diverging Track have effectively been removed, allowing the next turnout to start just past the frog, in effect creating overlapping turnouts and thus saving space. The Point End of the turnout has the normal three ties.

The No. 5c Lead Ladder turnout is generally used as the second turnout in a ladder track, after the turnout coming off the main line. It is also the opposite hand from the first ladder turnout.

Point End: When connected to a No. 5b turnout, the track spacing between the main line and the first body track is 2½ inches.

Frog End: A No. 5d or No. 5e turnout, of the same hand, must be attached to the Frog End of the No. 5c turnout.

No. 5d Intermediate Ladder

This turnout has the same shortened Frog End as the No. 5c, ending just past the frog and guard rails. At the Point End of the turnout, the Through Track and curved Diverging Track from the previous turnout has, in effect, been made a part of the No. 5d turnout. The two modified ends allow the No. 5d turnout to overlap the previous turnout and to be overlapped by the next turnout, thus saving space.

The No. 5d Intermediate Ladder turnout is usually used after the No. 5c turnout near the start of a ladder track or after another No. 5d to continue adding body tracks. Generally, a series of No. 5d’s are used — one after the other — for most of the body tracks of a yard making the No. 5d the most widely used turnout for most ladder tracks. The No. 5d provides 2-1/16-inch track spacing between body tracks.

Point end: The Point End of the No. 5d turnout must connect to either a No. 5c turnout or another No. 5d turnout, of the same hand.

Frog End: Another No. 5d or a No. 5e turnout, of the same hand, must be connected to the Frog End of the No. 5d turnout.

No. 5e Last Ladder

This turnout has the same Frog End as the No. 5b turnout, including the curved Diverging Track. The Point End of the turnout is the same as the No. 5d where the Through Track and curved Diverging Track from the previous turnout has, in effect, been made a part of the No. 5e turnout. This allows the No. 5e turnout to overlap the previous turnout, thus saving space. The No. 5e provides 2-1/16-inch track spacing between body tracks.

The No. 5e Last Ladder turnout is generally used as the last turnout on a ladder track.

Point End: The Point End of the No. 5e turnout must connect to either a No. 5c or No. 5d turnout of the same hand.

Frog End: The Diverging Track and the Through Track of the No. 5e become the last two body tracks of the yard (or a runaround track from the Through Track).

Conclusion

This track system made designing and implementing the Chesterfield Yard design enjoyable and pleasurable. Furthermore, the system performs very well, making the investment well worth it, for yards large and small. Consider it for your next project!