By Bob Chapman

With the increasing variety of accurate and reliable off-the-shelf locomotives and rolling stock, the model railroading hobby has moved toward operations as a primary focal point. Many of today’s operating sessions concentrate on freight trains — assembling them, moving them over the line, and switching their cars to various industries. More often than not, the passenger train is a run-through, staged primarily as a nuisance event for the freight train operators.

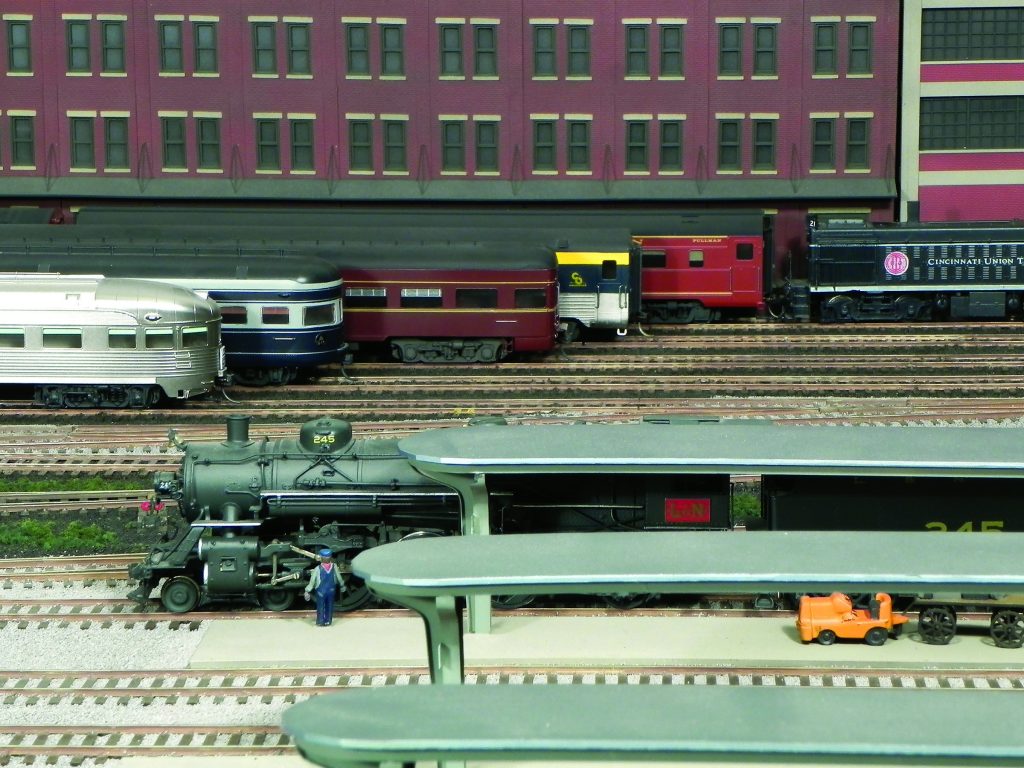

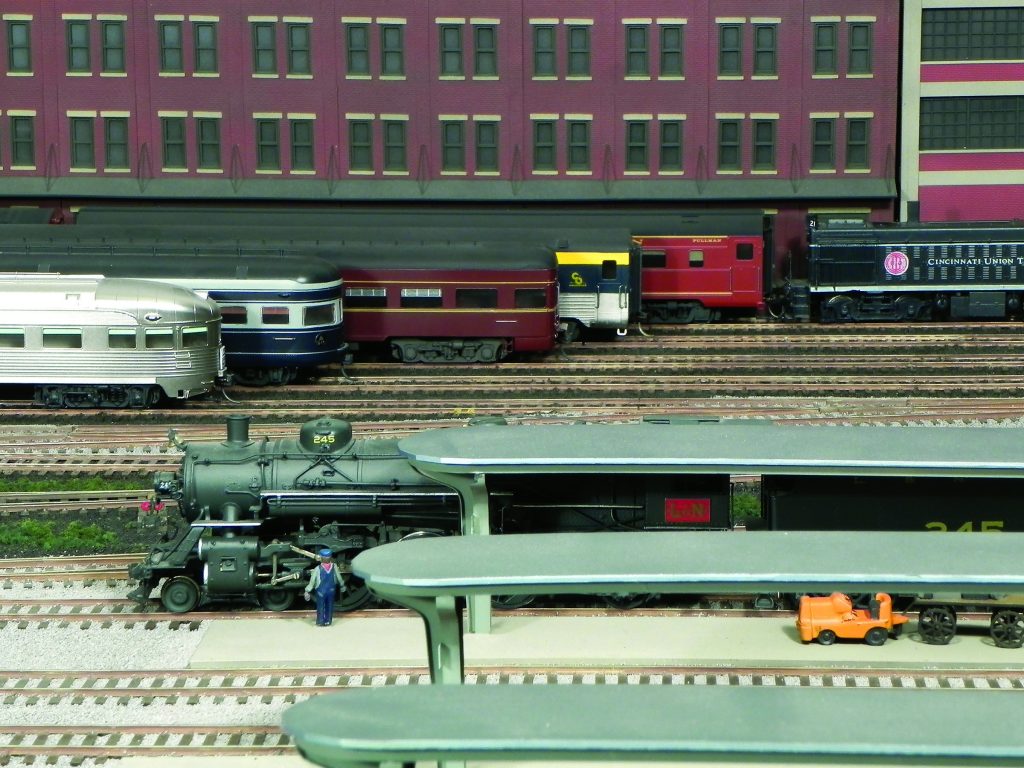

A passenger terminal can open an entirely new vista of passenger train operations. In addition to arrivals and departures, cars can be switched into or out of consists, trains can be turned and moved to storage yards for servicing, and locomotives turned, serviced, or swapped. A union station serving more than one road offers the opportunity for unusual side-by-side staging of locomotives and colorful, streamlined consists, as well as swapping cars between roads. The operational fun is further increased if matched to tight passenger train schedules.

A variety of wild-card events can be inserted to add operational challenge. A late train must be accommodated into the schedule and the facility. A long holiday consist of mail cars, coaches, and sleepers must be squeezed into available trackage. The railroad president’s business car must be switched onto the Limited. Or a “Boy Scout Special” needs a platform track and a motive power change from the limited pool.

Cincinnati Union Terminal featured a large terminal with 16 run-through platform tracks, which the author compressed to eight. A typical smaller terminal might have four tracks, with some or all stub-ended. In both cases, a separate short stub track might be provided for a layover of a sleeper, diner, or business car.

A major terminal requires significant space and must be planned during layout design, but the operational fun of swapping locomotives and cars can also be achieved in a small facility of a few tracks incorporated into an existing layout.

The passenger operations toolkit is simple. Public timetables show arrival and departure times, train consists, and locations where diners, sleepers, or coaches are added or dropped. Consist books, often available from railroad historical societies, include more detailed consist information such as the addition or removal of head-end cars.

The major terminal in my life was Cincinnati Union Terminal, jointly owned by its seven fallen flags: Baltimore & Ohio, Chesapeake & Ohio, Louisville & Nashville, Norfolk & Western, New York Central, Pennsylvania Railroad, and Southern Railway. As a fascinating part of my childhood, CUT featured an intermingled variety of colorful consists and motive power, prompting a lifelong interest in passenger trains and their operation. It was inevitable that my layout would need to feature CUT.

Exactly mirroring CUT’s operations and track plan would require massive space, but by prioritizing the major features I wanted to include, I achieved many of the important elements. Let’s take a look at “little CUT” and its operations…

Steam locomotives completing their runs would escape from their trains to a nearby locomotive facility to be coaled, watered, cleaned, turned, serviced, and placed on a ready track. For run-through trains, steam and sometimes diesel locomotives might be swapped for fresh power. Here, an inbound NYC Hudson is being turned for servicing at the roundhouse, after which it will be moved to an open-air “ready track” to await its next assignment. A union terminal’s intermingled power is always an interesting display — both on the prototype and model.

Collaborating railroads established interline sleeper routes to eliminate the need for passengers to change trains between major trip endpoints. In one of several CUT examples, Pennsylvania Railroad and Louisville & Nashville coordinated a pair of sleeper routes between New York City and Nashville or Memphis, Tenn. Both railroads supplied the cars, with L&N-owned cars painted Pennsy’s Tuscan Red to match the consist on Pennsy’s major share of the combined route. Westbound, the cars would arrive at CUT on Pennsy’s Cincinnati Limited at 8:30am and be promptly switched to L&N’s Pan-American for its 9:00am departure from an adjacent track. On our layout, this task is handled by one of CUT’s unique Lima-Hamilton 750-hp switchers.

Cincinnati had large Railway Express Agency and postal facilities adjacent to CUT, with many trains entering the terminal fielding one or more REA or railway post office cars to be switched to them. After unloading, the cars would again be switched to a head-end car storage yard to await their next assignment. While most of the RPO cars were standard heavyweights in the colors of the owning railroad, the REA cars were a diverse assortment, ranging from home or foreign road heavyweights and express boxcars to REA-owned express boxcars or reefers. Here, one of CUT’s ex-NYC 0-6-0 positions an arriving express car at the REA building.

Terminating trains needed to be turned. In Cincinnati, a reversing loop circled CUT’s roundhouse — a case where the prototype suggested the ideal modeling solution. Incorporated in CUT’s loop was a car washer, guaranteeing a sparkling consist with clean windows for outbound passengers. CUT 0-6-0 turns NYC’s home-built Mercury in preparation for its 3:30pm departure for Cleveland.

Once turned, the consist would be retired to the storage yard for cleaning, servicing, and provisioning. Perhaps an hour before departure, the consist would be switched to its departure track, to be joined there by head-end cars and the locomotive. It’s mid-day in the coach yard as a CUT switcher shoves Norfolk & Western’s Pocahontas consist onto its service track. Other trains rest nearby awaiting the call to service. While the platforms are now quiet as L&N’s local No. 7 awaits its highball, the evening rush hour will soon begin!

This article appeared in the April 2019 issue of Railroad Model Craftsman! Subscribe Today!

This article appeared in the April 2019 issue of Railroad Model Craftsman! Subscribe Today!