“HOTSHOT — Train with very high priority compared to other trains. Other than passenger trains, Union Pacific hotshots are intermodal trains that maintain the most expeditious schedules.”

“HOTSHOT — Train with very high priority compared to other trains. Other than passenger trains, Union Pacific hotshots are intermodal trains that maintain the most expeditious schedules.”

That’s how Union Pacific defines “hotshot.” As it notes, these days hotshots tend to be intermodal trains, loaded with containers and trailers jam-packed with consumer goods on a tight delivery schedule from shipping companies like UPS and FedEx. But more than a century ago, the hottest trains on the railroad weren’t loaded with containers with iPhones and packages but instead with milk that needed to get to consumers quickly before it spoiled.

In the early 19th century, most of the milk consumed came exclusively from local sources. In small towns and more rural areas, the milk came from cows owned by local farmers, but in more urban areas it might come from cows owned by local distilleries. The cows were fed swill, a liquid diet of residual mash from the alcohol-making process. For the distilleries, it made good economic sense to use the waste mash to make milk and get a little more profit, but the conditions the cows were kept in were not always ideal. Sometimes the cows would get sick and produce bad milk. Not wanting to waste anything, though, the distilleries would whiten it with plaster or thicken it with starch and eggs. Needless to say, it wasn’t exactly the healthiest stuff, and a New York Times investigation of the day found that “swill milk” was killing infants.

But with the advent of the railroad, the milk Americans were consuming — specifically, those living in large metropolitan areas — started to change. Fast trains were able to quickly and efficiently ship dairy products from local farms to cities twenty, fifty, or even a hundred miles away from the source. According to a story by James A. Kindraka, New York City, Boston, and Baltimore were among the first cities to see milk trains starting in the late 1830s and 1840s. Due to milk’s perishable nature, railroads had to move it quickly, so carloads of dairy were often added to passenger trains or run as their own individual train. Not only were they the original hotshot, you could consider them the original unit train, too.

Over time something called a “milk shed” would develop around an urban area, almost like a watershed for a reservoir. Milk from farms upstate would travel down the rails like rivers to nourish thirsty city-goers. As railroads improved, the milk sheds would expand. One dedicated operation was the “Rutland Milk” that forwarded deliveries from dairies in Vermont direct to New York City, a distance of more than 200 miles. Rutland Railway would hand off this train to New York Central at Chatham, N.Y., which would then run express down the Harlem Division direct to 60th Street Yard in New York City.

Further north, on the Boston & Maine, milk was big business. The Boston “milk shed” stretched north into Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine (via Maine Central), and even into Quebec. It also stretched west to the Berkshire Mountains of Massachusetts and into eastern New York State. Milk consumption was on the rise in the early 20th century and from 1911 to 1912, demand literally doubled in Boston, from 90 million quarts annually to 180 million quarts.

Railroads used different types of equipment to move milk. In some instances, they employed traditional ice-cooled refrigerator cars loaded with cans or crates of milk. Unique glass-lined “butter dish” tank cars (so named for their shape) were developed in the 1930s to transport milk. Some shippers experimented with milk tanks that could be moved on a flatcar or a truck, an early version of intermodal technology. Cars were either owned by the dairies, leasing companies, or the railroads themselves. The entire operation varied from region to region and railroad to railroad.

The arrival of trucks and an improved highway system brought to an end the railroad industry’s monopoly on dairy traffic in the years following World War II. In some places, that transition started earlier. In 1915, railroads moved 84 percent of Detroit’s milk; a decade later, that had dropped to just 11 percent.

The milk train would last the longest in New England, one of its original strongholds. Boston & Maine would move milk well into the mid-20th century, thanks in part to strong partnerships with regional dairies. In fact, the last scheduled milk train was run from Eagle Bridge, N.Y., to Boston in August 1972!

For more information, seek out James A. Kindraka’s article “Milk Run! The Story of Milk Transportation by Rail” in the January/February 1990 issue of the National Association of S Gaugers journal Dispatch. As of late 2021, a version of it can be found online.

—Justin Franz

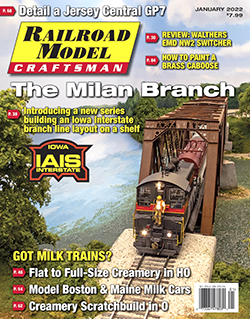

This story appeared in the January 2022 issue of Railroad Model Craftsman. Subscribe Today!