By Gaylord Gill/photos as noted

By Gaylord Gill/photos as noted

My Buffalo & Chautauqua layout represents portions of Pennsylvania Railroad’s Northern Division in 1953. I have enjoyed doing research in my attempt to convey a particular sense of this specific road, location, and era. In particular I’m a structures guy, and one model I have constructed is an interlocking tower which was located in Buffalo, N.Y.

FW Tower controlled a triangle of trackwork where routes of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Erie Railroad, and Buffalo Creek Railroad all crossed each other. Based on diagrams and one interior photo, FW had as many as 35 levers to handle all the turnouts and signals. Although the Erie built and owned the structure, both Erie and PRR jointly operated it.

Since FW controlled some of the Pennsy trackage I was portraying, I decided a model of it belonged on my layout. Once I saw a vintage photo of this unique building, I realized it could be a signature structure on my layout. The first feature that stood out was the castellated end walls, with the stair-step caps at the top. The second feature was the blocks which form the walls – while standard cement blocks are typically 8” high by 16” long, FW’s blocks were clearly longer.

We’re into the first few days of Conrail operation at FW Tower as a transfer run from Bison Yard to Frontier Yard led by former Penn Central SW1500s clatters across the diamonds in April 1976. The track in the foreground is the Buffalo Creek Railroad, while the other track crossing in front of the tower is the old Erie Railroad line to downtown Buffalo, cut back to an industrial spur. —Ken Kraemer photo

Even though I model in S (1:64), I doubt there is a kit in any scale that could be a reasonable starting point for this project. Because of the unusual proportions of the blocks, there isn’t even an appropriate sheet material available. Creating an accurate model would involve scratchbuilding.

Laser-cut Parts

In discussing the project with my friend Jamie Bothwell, he proposed an excellent approach: he would lay out the walls and windows of the structure and then cut the pieces for me on a laser machine. Jamie had been experimenting with the laser at a lab he had access to, cutting out sides for S scale passenger cars, and he wanted to try a structure project. I of course jumped at his offer. Since the two of us live 600 miles from each other, we began a series of email exchanges to work out the plans.

From reference photos in books and on the internet, Jamie and I collaborated to determine the dimensions of the blocks which make up this structure, using the fact that standard entry doors measure out at a height of 6’8”. We concluded the blocks measured 8×24”. Jamie then used computer-aided design (CAD) software to create elevation-view drawings of FW tower’s four walls. CorelDraw was the package he used, and the tool differentiates two types of lines in the drawing. The first type, used for all the mortar joints in the walls, tells the laser to etch, while the second type tells the laser to cut all the way through.

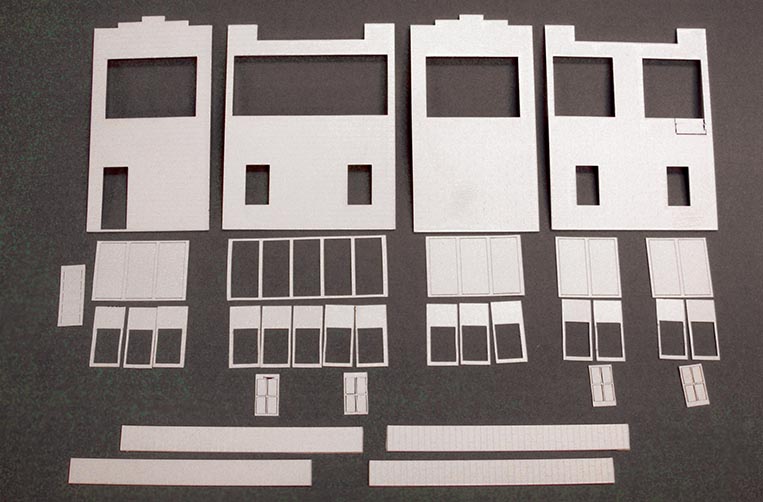

To kick-start the scratchbuilding of FW, friend Jamie Bothwell laid out and cut these parts on a laser cutter. The walls were made of .060” styrene, and the laser machine also etched in the mortar lines of the block pattern.

Once he had the elementary dimensions of a prototype block, Jamie used the CAD program to draw an exact S scale equivalent of it. He then began to lay out the walls of the structure by counting blocks in the photos and duplicating the same pattern in the CAD drawing. Wherever possible, he simply copied and pasted patterns he had used earlier. As Jamie says, “Drawing on the computer isn’t any faster the first time through. Where you save time is in the subsequent revisions, and any duplicating steps.”

After laying out the four walls, Jamie created window frames which would exactly fit the openings in the walls. Each of the first-floor frames was a simple four-pane part, while the second-story windows consisted of inner frames and outer frames. Jamie also created the chimney sides in the same block pattern, plus a five-panel entry door for the first floor.

In fairly short order Jamie had completed his digital drawing of FW, and he then ran his CAD file into the laser to produce the 33 parts he had planned. Per our discussions, he cut the four walls out of .060” sheet styrene, while the other parts were done in .020” styrene. Because the first-floor window frames had such a narrow profile, Jamie cut those from Laserboard, a resin-impregnated paper. Within a week he had mailed me a package of parts.

While these laser-cut parts provided a huge jump-start on this project, what Jamie produced was certainly not a complete kit. The rest of this article will hit the highlights of the steps I followed to build my model of FW tower…