By Gary Petersen/photos by Dan Munson

By Gary Petersen/photos by Dan Munson

Most model railroaders build more than one railroad over their lifetime. When the time comes to move, we can easily move the locomotives and rolling stock; we can even do this with many of the structures and some scenery. Not so much with larger sections of the railroad. As much as we try, removing a favorite section of an old railroad, moving it across town or across country, then integrating the section into a new layout, doesn’t work in most cases.

There are rare times that this can be accomplished. The Salt Lake Southern Railroad (SLS) is a successful example of this. I started the SLS in our new home in suburban Salt Lake City in the early 1980s. I began with a section of the original railroad that we brought with us from Omaha. This section became Sage, Utah, on the SLS and is still in use today.

The SLS requires 14-16 people to operate using car cards and waybills and CTC signals for authority. Road trains have an impressive mix of power including locomotives from the SLS, Union Pacific, Chicago & North Western, and Western Pacific, just to name a few.

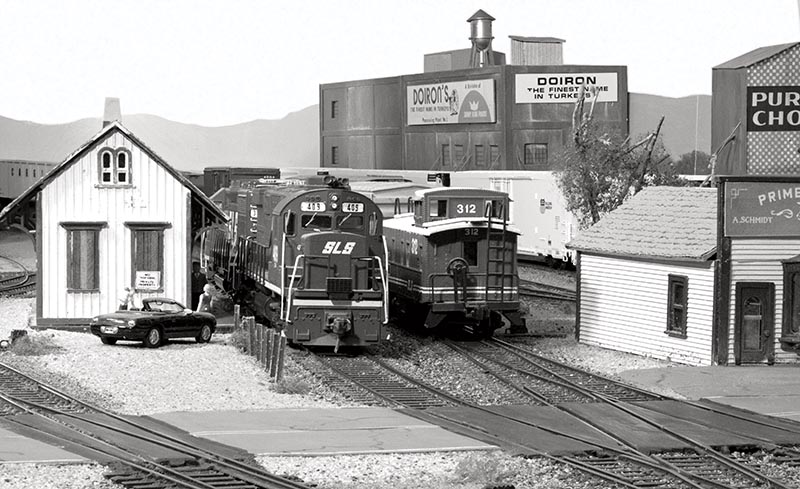

Salt Lake Southern’s Atlantic City local is running around their train in their namesake town. The SLS C424 409 and an EMD Geep will take the train back to the yard at Riverton, Wyoming.

Freelanced History

In the late 1880s, the original Salt Lake Southern Railroad began to lay track from Salt Lake City toward Texas. With the stiff competition from the Utah Belt Railroad, traffic never reached the levels that management had expected. The board of directors decided to look eastward for a new connection with the Chicago & North Western at Lander, Wyo.

In 1911, construction began on the new line north through Ogden and continued further north to the Bear River. From here it followed the river valley all the way to Sage Junction, Utah. At Sage it crossed into Wyoming and more or less followed the wagon train trail over South Pass and into Lander. It took two years to reach Lander with traffic levels increasing monthly ever since.

In 1920, the Western Pacific looked to the Salt Lake Southern for a possible new connection and in 1921 they both agreed on mutually beneficial terms. This new SLS line gave the Western Pacific its second connection to the East.

The new route of the C&NW, SLS, and the WP never had a grade that exceeded 1 percent. The big exception was the SLS route over South Pass. This portion of the railroad had a 2.75% climb on the east side and a 2.85% on the west side. This part of the new transcontinental route would have to have helpers, which was something I had planned from the start.

Chicago & Northwestern GP30 821 and GP7 1774 pair up on the C&NW local at Lander, Wyoming, working the Rickman Cement plant. Lander is the original end of trackage for CNW.

Equipment

My son Marty Petersen decaled all of the SLS home road equipment. That was a huge time saver for me. Next on our “to do” list is to weather engines and rolling stock. This should be a big help in making the railroad look more realistic.

Helper operations were originally done with a separate crew member running the helpers. However, this presented a problem of too many people in too small a space. Operators were competing for physical space, and verbal communications were a real challenge. The helpers are now added to the head of the consist and push on the rear of the train, which is easy to do with my NCE DCC system.

Standing next to your train as it climbs a grade is a real treat. My TCS WOWSound decoder in the front set of engines automatically notches up when it starts up the grade, then the sound fades away as the head end consist gets farther from you. About that same time you start to hear another set of engines getting closer, it’s the helpers on the rear. They soon pass and near silence returns to the scene. Now this is mountain railroading!