By Otto M. Vondrak/photos by the author

By Otto M. Vondrak/photos by the author

How many opportunities do you get for a “do-over?” That was the situation presented to the members of the Rochester Institute of Technology Model Railroad Club (RITMRC) just a few years ago as the hard decision was made to tear down the original HO scale layout that dated back to the club’s beginnings. Building a model railroad of any size is always a learning process, let alone for a club with regular turnover and a range of interests and modeling skill. What lessons could the club take away from that important first effort to make the next one even better?

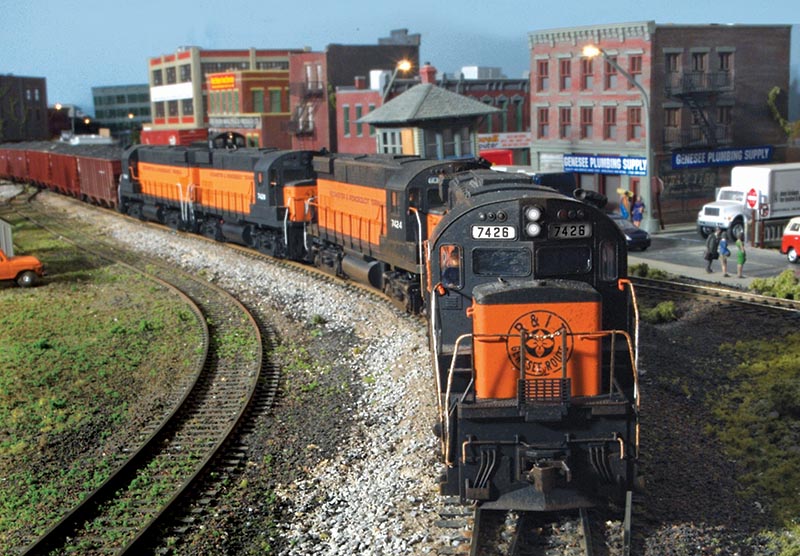

The model railroad club was founded in 1996 in the same tradition as others at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Penn State, Purdue, and Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Over the years, the club developed the concept for a proto-freelanced line called the Rochester & Irondequoit Terminal, a play on the school’s initials and adopting our alma mater’s color scheme of orange and black. The R&IT is a modern regional short line that connects the upstate cities of Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse. The first iteration of the “Genesee Route” was an imagined patchwork of fictional interurban routes and cast-off branch lines connected by Conrail trackage rights.

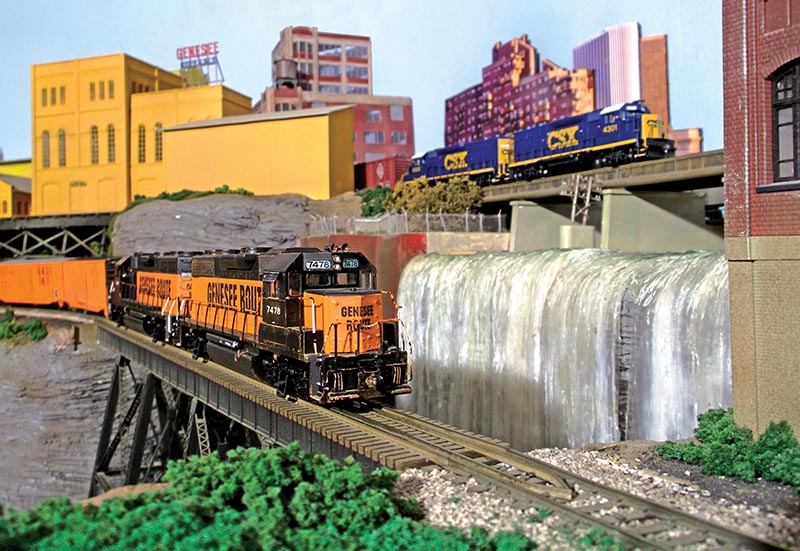

An R&IT local train crosses the tall steel trestle over the Genesee River while a westbound CSX freight crosses over the top of High Falls in downtown Rochester. The placement of the Genesee Brewery, the waterfall, and the two railroad bridges are all based on the layout of the actual scene in downtown Rochester, though significantly compressed to fit the available space. The backdrop featured photos of actual downtown buildings that were cut out and applied to foamcore to give them some dimensionality.

After some shrewd campaigning, the club was awarded a recently vacated office under the auditorium stage, with the restriction of only occupying half of the oddly shaped room in case another school club was to move in with us. As much as the club wanted to replicate the Conrail action members were quickly becoming familiar with, a sweeping four-track main line was out of the question.

Early Designs

Our measured space was roughly 10×25 feet, which may not seem very big, but it was larger than any layout any of us had built previously (if any of our members had built one at all). Fortunately, our club advisor was an experienced hobbyist who understood the need for a long main line run in order to hold our interest. Prof. Jim Scudder used his experiences from the Kodak City Model Railroad Club as well as his own freelanced home layout to help guide the design of the first R&IT.

We quickly determined return loops at either end of the main line would facilitate continuous running, which was important to our young club. Those loops representing the endpoints of Buffalo and Syracuse would be connected by a single-track main line that would make two laps of the space, gradually climbing the entire way. It was a design that would have made John Armstrong bite his lip as he cracked a smile at our blind determination. The club essentially designed a double-deck railroad where all the levels were compressed onto the same viewing plane. Carefully planned view blocks and creative scene design helped make the multiple levels of track appear plausible. A switching district that the club named “Red Onion” provided some operational interest, while the rest of the layout included scenery both urban and rural to simulate greater distances.

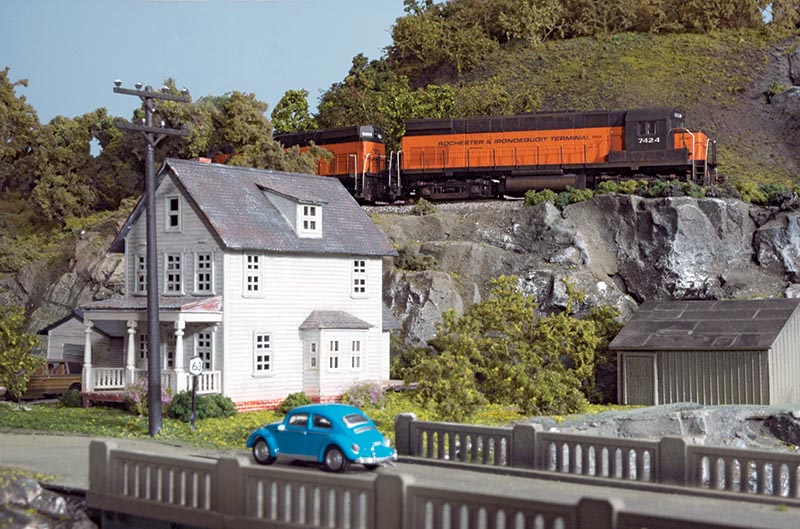

A road freight approaching Alexander rattles the windows of homes in the village of Scudderville. This rural scene was named after our first club advisor, Prof. James F. Scudder, who passed away in 2014. Variations in scenery helped promote the illusion of greater distances on this small 10×25 layout.

A road freight approaching Alexander rattles the windows of homes in the village of Scudderville. This rural scene was named after our first club advisor, Prof. James F. Scudder, who passed away in 2014. Variations in scenery helped promote the illusion of greater distances on this small 10×25 layout.

A large yard dominated the front of the layout, which was assigned to represent Goodman Street Yard in Rochester, though dramatically scaled down. The yard consisted of three arrival/departure tracks. Four classification tracks made up the rest of the yard. The original engine facility was a modern two-stall engine house flanked by sand and fueling tracks (See “Modeling a Modern Sanding Facility,” February 2002 RMC). In concept, this design would have been adequate for modeling most short line operations. In practice as a yard for a club, it crippled our railroad to the point of standstill.

While the design would be perfectly acceptable for a modest home layout, the club members quickly outgrew the design. There wasn’t enough room for all the engines members wanted to use and display. Goodman Street Yard quickly filled up with stored cars. While an eight-car local might be fun to switch, most of our members wanted to run long freights like the ones observed running past our campus. A decent 24-car freight could be assembled, but you would tie up the entire yard doing so. And forget about running passenger trains of any decent length. Goodman Street Yard was classification, staging, and storage all in one—and woefully inadequate for all…