by Alan Bell/photos by Craig Wilson

by Alan Bell/photos by Craig Wilson

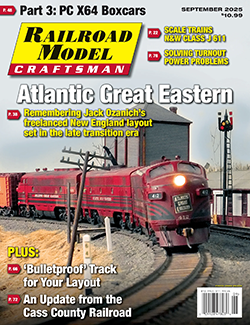

Conceived in the fictional boardrooms of the Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, and Lehigh Valley railroads more than a hundred years ago, the Atlantic Great Eastern served the great states of Maine and New Hampshire and their rural communities for multiple decades following the Great Depression. For years, John “Jack” Ozanich promoted the construction of a bridge route stretching from Maine’s northern region connecting Canadian Pacific and Bangor & Aroostook to the western tip of New York State with connections to Lehigh Valley and New York Central. His route would provide a means to efficiently transport the region’s abundant forest products and potato harvests to a growing nation, while providing a shortcut for Great Lakes freight traffic destined for northern New England.

The idea was simple; however, the construction proved a challenge given New England’s geology and harsh winters. Ever the optimist, Jack found his engineering champion in John “Mel” Korstange who supervised the railway’s construction. With many helping hands, the Atlantic Great Eastern began to take shape, albeit in HO scale in Jack Ozanich’s basement.

ABOVE: The crew of the South Dover Tramp Job has pulled up alongside Stosh’s Workingman Café located in the City Yard industrial area. The diner is named after a real place in Battle Creek, Mich,. frequented by Grand Trunk Western crews.

The Atlantic Great Eastern was divided into two divisions, Western and Eastern. Both divisions operated on single-track main line with passing sidings at the various towns scattered along the serpentine route that followed numerous New England rivers. The Western Division ran from Auburn, N.Y., to Berlinton, N.H. This route paralleled New York Central’s Mohawk Division until reaching Utica, N.Y., then gradually pushed north into Vermont after crossing the southern portion of the Adirondack Mountains. Once in Vermont, the line’s ruling grade was managed in similar fashion as the Delaware & Hudson and Rutland railroads had constructed winding through the valleys of the Green Mountains. Once in New Hampshire, it was the White Mountain terrain that presented the greatest construction challenges.

The Eastern Division ran from Berlinton, N.H., to Guerette, in the northern tip of Maine. Passage across the New Hampshire and Maine border at Mahoosic Notch was the greatest civil engineering challenge the construction crews endured. The 3.5-percent main line grade was a challenge to both train crews and dispatchers, but a joy for railfan photographers. The Eastern Division was quintessential New England railroading at its best, both rugged and picturesque.

From its beginning, the appearance and operation of the Atlantic Great Eastern followed that of its three corporate owners. Ownership was divided by CN (30%), CP (30%), and LV (40%), and the Atlantic Great Eastern served to move bridge traffic for its owners, bypassing congested terminals in Albany and Boston. The Atlantic Great Eastern interchanged with numerous other railroads, generating considerable traffic for the otherwise modest railroad. Connections included Allagash Railroad (AGR); Bangor & Aroostook (BAR); Boston & Maine (B&M); Canadian Pacific (CP); Central Vermont (CV); CN subsidiary Grand Trunk (GT); Delaware & Hudson (D&H); Delaware Lackawanna & Western (DL&W); Maine Central (MEC); New York Central (NYC); Portland, Gray & Northern (PGN); and Rutland.

ABOVE: Extra 590 East is departing Danhill, N.H., in the late winter of 1965. The arrival of GP18 and SW1200RS units in 1960 spelled the end for steam power on Atlantic Great Eastern. These new diesels also introduced a new paint scheme with black-white chevrons on the nose.

The railroad’s physical plant was significantly influenced by the parent companies, especially transition into the diesel era with equipment, choice of color and decorating elements. In the days of steam, the railroad employed the shorter wheelbase Consolidations and Mikados to negotiate a main line void of tangent track and low-load-capacity bridges. As the railroad transitioned to diesels, venerable Alco FA cab units and RS-series road switchers worked alongside EMD F-units and Geeps. Second-generation Alco RS-36 and C-424 units appeared in the 1960s. Likewise, in the later years the wood-framed buggies (cabooses) were replaced with upgraded steel cars from International Car Company.

The traffic movement across the Atlantic Great Eastern was very seasonal. Pulpwood shipped primarily in the winter, when loggers were able to work the forest without being impeded by the thick New England mud. The potato rush started in November, running through to March. Many a solid block of AGE refrigerator cars would traverse in both directions — loads west, empties east — carrying their cargo to all parts of the country. The Atlantic seaport at New Landsport was also a destination for reefer trains. A variety of other commodities such as textile, dairy, merchandise, fuel, and less-than-carload team track cargo filled the railcars moving across the Atlantic Great Eastern.

The trains that ran the daily schedule were relatively few in number, mostly slow moving freight, over a single-track main line. Train orders controlled movement with the eastward direction being superior. To help the dispatchers during the seasonal rush, the timetable listed several fourth-class regular trains in the westward direction. The only first-class regular trains running in both directions were No. 5 and No. 6, the daily passenger train. Train 6 was famous for its “lobster car,” an express reefer originating at New Landsport.

ABOVE: Extra AGR 101 West crosses the Dead River bridge at Bolton Mills. This twice-weekly pulpwood train was a joint operation between the AGE and Allagash Railway. It delivered pulpwood loads off the Clayton Lake Subdivision to the paper mills at Berlinton, N.H. The AGR Alco RS-1s were built by Mike Confalone (see January 2025 RMC for more about Allagash Railway).

Dispatching was most interesting on the Eastern Division’s South Dover Subdivision with helper movements over Mahoosic Notch and traffic to and from the Atlantic Ocean seacoast via the New Landsport Subdivision branch at Rangeley River Junction. Movements over Mahoosic Notch required so many train orders that the railroad installed centralized traffic control (CTC) in the later years between Rangeley River Junction, Maine, and East Berlinton, N.H. The CTC system based on General Railway System (GRS) designs significantly improved the traffic flow, especially during the winter months.

For many years AGE was a formidable fixture in the towns through which it passed. Like its counterparts, the railroad followed the economic development and changes of the nation. In the days of steam, daily milk trains picked up reefers from the creameries to be forwarded to Boston via Maine Central, but that traffic was eventually lost to trucks in the 1960s. The passenger consists with their plush varnish coaches gave way to the Budd RDC and eventually the automobile. Passenger train schedules were maintained into the 1960s, but by then freight traffic was mostly TOFC and merchandise cars as pulpwood and potato traffic dropped off considerably. Eventually, the rule of the railroad would be replaced by more modern transportation methods and the Atlantic Great Eastern would be a forgotten memory.

Although never a prototype railroad, the Atlantic Great Eastern was Jack Ozanich’s time machine. His Atlantic Great Eastern was a means to recreate the past and relive the pinnacle days of railroading during the late mid-century transition era. To understand the Atlantic Great Eastern, one first has to understand its creator. Jack was born in June 1943 in of Paw Paw, Mich., located at the end of a Chesapeake & Ohio branch line (and the mighty New York Central was a few miles away at Lawton). As a young boy, he spent countless hours watching train crews work the small towns in Lower Michigan. The crews would invite him on rides and give him discarded switch lists as souvenirs. He witnessed the last days of steam and was fascinated by both the equipment and the jobs people performed. The army came calling in 1962 and Jack spent two years as a radio operator in Germany, where he often chased steam trains on his days off. After an honorable discharge he hired out on Grand Trunk Western, first as an operator at Schoolcraft, Mich., joining the men he watched as a young lad. He moved into train service as a fireman and then locomotive engineer. Jack was a professional railroader, through and through. Consequently, Jack created and operated the Atlantic Great Eastern as a real railroad. It was his vocation and avocation all in one…