by Phil Monat/photos by the author

by Phil Monat/photos by the author

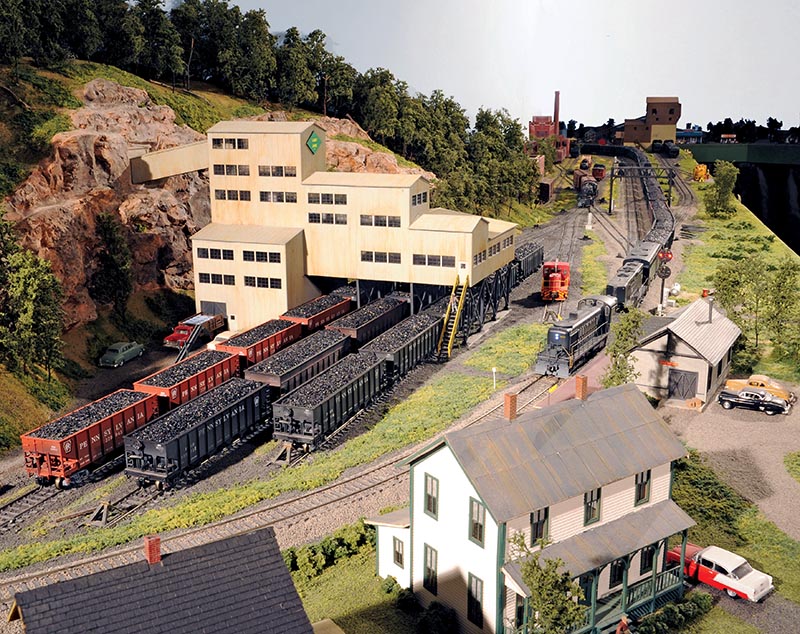

Professional railroader Steve Mallery has several reasons for modeling Pennsylvania Railroad’s Buffalo Line. Growing up in New Jersey, he developed his fondness for the unique infrastructure, wide variety of equipment, and those distinctive position-light signals that are all trademarks of the Pennsy.

Steve went to work for successor Penn Central as dispatcher in 1973, moved on to Conrail in 1976, and ended his career with Norfolk Southern. When time came for him to start his own layout — after the Conrail’s 1999 breakup and his transfer by NS to Harrisburg, Pa. — he chose to model PRR. Key to his choice was a desire to prototypically model the prototype operations of long, heavy trains in a challenging environment.

Steve already had extensive experience in building layouts by the time he started his own. He’s a member of The Model Railroad Club of Union, N.J. (his father, well-known author and modeler Paul Mallery, was instrumental in founding the club in 1949). Steve was one of the key people behind the design and construction of the HO scale layout, particularly its interurban railroad, The Trenton Northern Traction & Light Co.

ABOVE: Train EER-1 has stopped short of the signal for its crew change as it prepares to continue east down the hill to Renovo. In Steve’s professional life, crew changes and hours-of-service were critical parts of the reality of operations, so it was a natural for him to model this ritual.

When Conrail moved his dispatching office south to Mount Laurel, N.J., Steve started work on his own layout. With his subsequent transfer to Harrisburg, Steve was able to devote all of his energies to building his version of the Buffalo Line in HO scale. It didn’t hurt that NS also assigned the real life Buffalo Line to Steve’s desk, so he had the ultimate insider view to the railroad and how it worked.

Given his focus on prototype operations, Steve has other reasons for choosing this PRR route: its mostly single track status, and that it hosted a mix of unit and manifest freight trains with just a little passenger traffic. It is also a fully signaled railroad, which translated to centralized traffic control (CTC) for modeling purposes. All of this keeps the dispatcher busy, something Steve enjoys, while the famous Keating Summit grade requires helpers, adding further work for the dispatcher. In addition to slowing down trains and adding operational complexity with helper moves, the grade also provided another important advantage: It eliminated the need for a helix.

ABOVE: A westbound unit coal train starts up the Keating Summit grade at Driftwood, Pa., which the railroad refers to as DRIFT. This is the base of the grade, where the railroad goes from double to single track.

Steve’s operational focus made main line run length critical (it is currently 260 feet). He found that by increasing the 2.6 percent grade to 3 percent, he could gain the increased main line length a second level offered without employing a helix. Helixes pose several challenges for operations, including the length of time the train is out of sight (a problem with long and heavy trains) and the huge amount of space they consume. Using the Keating Summit grade as the visible and modeled transition between decks was a considerable advantage.

The two decks also help support another of Steve’s goals: that only one main line can be seen at any given time per section of benchwork. He did not want multiple tracks from different lines stacked next to each other on the same level. This aids in directional consistency (north is always to your left) and avoids any confusion in terms of which main you might be on. And this is, generally speaking, more prototypical, which is the bottom line for Steve.

ABOVE: The west end of Renovo is always busy with the yard drill crew working its short lead. Getting head room is a challenge due to conflicting traffic – in this view Train EB-2 is about to take the approach signal while a westbound passes by the station. EB-2 will have a set-out and a pick-up, while the westbound will have the same from the other end of the yard.

Steve wanted above all else a user-friendly layout. He keeps reach-in distances a reasonable 23 inches on the lower deck and 11 inches on the upper, while the 37-inch-wide aisles with wider passing areas make following your train a pleasure. The lower deck is 36 inches off the floor, while the upper deck is at 55 inches. With allowance for framing, this leaves a minimum of 14 inches between decks. All signals are visible from the aisle, as well as being displayed on remote panels up high on the backdrop. The minimum radius is 38 inches, with all main line turnouts being No. 8, while No. 6 serves industrial, yard and staging trackage.

For any layout heavily focused on operations, staging is critical. The Buffalo Line track plan provides the extensive staging required to generate prototypically sized trains. Enola has a capacity of 231 cars, Newberry can hold 59, Erie can fit 216, and Buffalo will hold 291. The staging is a stub-ended “shotgun” design, with multiple trains on each track. A very well-thought-out operating plan and a careful lineup minimize any conflicts…