By Keith Wills/illustrations by Dave Snyder

By Keith Wills/illustrations by Dave Snyder

Keith Wills authored our Collector Consist column for more than 30 years. We thought you would enjoy this early article from December 1983! —Editor

Trains and Christmas have always been an integral part of my life, and the two were entwined in an annual ritual which was repeated at year’s end from when I was quite small until about the time I finished grade school, a ritual which my father and I shared in that unique bond that an exist when father and son are inextricably joined by a common love for trains.

What had been originally pre-Christmas trips into Manhattan to visit Macy’s Santa Claus expanded as I grew older, to include train showrooms and hobby shops, as my burgeoning interest gained in enthusiasm—much to my father’s delight.

As fall advanced into winter, and the days grew shorter, the air in our house became charged with vibrant anticipatory excitement at the impending journey into the city, heightened by pouring over some catalogs my father had been able to get his hands on during that austere wartime era. New trains were not generally available, with manufacturers’ efforts being devoted to material needed overseas, so where he had gotten his 1940 and ’41 American Flyer catalogs, I’ll never know. When Saturday morning breakfast was finished and the dishes cleared away, the catalogs would be placed upon the enameled metal tabletop, their pages spread open for us to examine in the minutest detail. They were a revelation to me.

I had an oval of O-27 track in the basement under my father’s fishtanks, upon which ran my black Commodore Vanderbilt freight of which I was very proud, and from which I received much enjoyment. American Flyer’s better O gauge trains of that era were diecast scale detailed models, both in locos and cars, and my poor Marx set never looked as good to me again. My pleasure in that lithographed set diminished by comparison. I could ask Santa for a new train, not daring to ask for such expensive largesse from my parents. I was torn between the glamorous beauty of the bullet-nosed Royal Blue, or the dramatic brute strength of the top-of-the-line Union Pacific 4-8-4. I always had expensive tastes, and therein lay my dilemma. My parents couldn’t afford a new train, let alone try to find one.

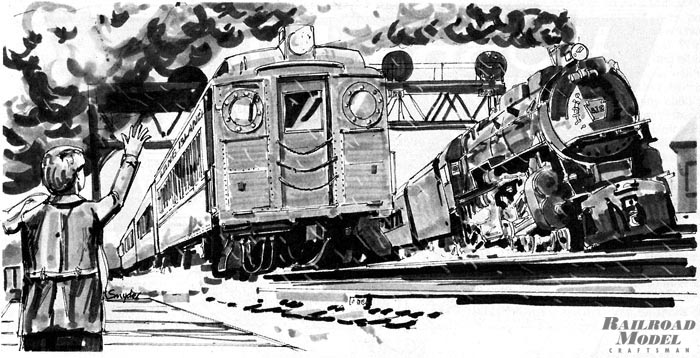

On the appointed day we were to journey into Manhattan, we bundled ourselves against the cold, damp winter air, and walked to the Belleaire station on the Long Island Rail Road. My father, having bought our tickets, waited in the station, while I preferred to brave the cold on the platform, where I could see over the rooftops with their smoking chimneys, rather than choose to wait in the warm comfort of the drab waiting room. Standing near the platform edge, I looked in either direction hoping to espy any train that might hove into view. I knew if a tiny speck appeared on the center express tracks, it would grow into a smoke belching steamer that would thunder past us in a flash of furiously spinning rods and pounding drivers, with blurred faces at the windows of the coaches being pulled in the wake of this noisy behemoth.

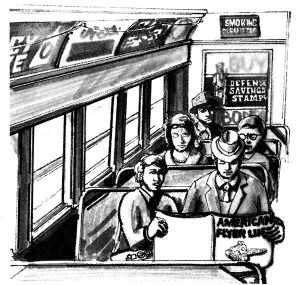

Our train was a more sedate string of scruffy, elderly MP54 electric m.u.’s which would arrive more graciously as befitting their antiquated status and slide to a halt. Once inside the car, I deemed it necessary to run ahead down the aisle, hopefully to find a window seat on the express track side, all the better to see any passing trains. The train seemed filled with other children taking their parents into the city for the pre-Christmas sights, their faces happy with eager anticipation. After a few stations, we pulled into Jamaica, that bustling transfer point where different lines from the island funneled into and through the multi-platformed station, sending them on to terminals in Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan.

Jamaica was always alive with activity, particularly at this holiday period, with loudspeakered announcements of arrivals and departures, and people detraining and changing platforms and hustling aboard other trains. It was also a great place to train watch. There were strings of the newer double deckers, there were G-5’s sitting patiently under steam, waiting to depart for those areas of an-electrified Long Island; and there was always the possibility of seeing a cat-whiskered DD-1 electric, or even catching a glimpse of one of the dumpy boxcab diesel halves, Ike or Mike, as they were affectionately known by Long Island employees.

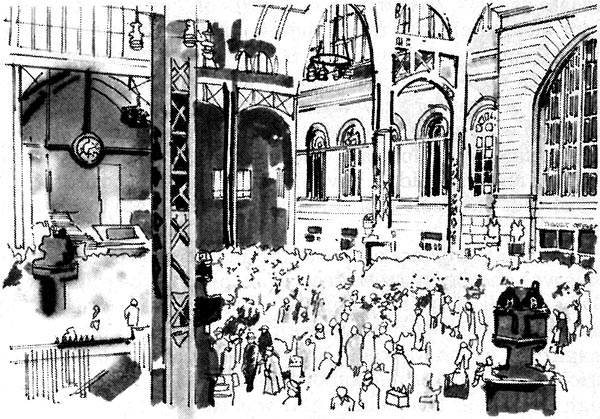

Once on the Manhattan-bound train, my imagination took flight, and I conceived of myself as master of the track and trains, simultaneously being able to operate and ride the train, perhaps a secret dream of every model railroader. Slowing down through the Long Island City yards, it was possible to view passenger equipment of the many roads using Penn Station sitting in long frigid lines on their sidings, with GG-1’s standing in serried ranks waiting to pull the empty trains into the passenger terminal across the river. Our train plunged into the tunnel under the East River, and, after what seemed an eternity, emerged into the smudgy, dank bowels of Penn Station.

Penn Station flowed with parents and children, alive with their expectant electric energy, all heading for the same destination, Macy’s, with its fabulous animated window displays, outside of whch adoring families cheerfully chose to freeze in the numbling cold on a windy 34th Street, all the while absorbing the Christmas magic to be seen in the windows as the elaborate floats passed in mechanical precision.

After two bone chilling viewings, my father and I would enter the claustrophobically crowded main floor. In contrast to our frigid experience outside, it was suffocatingly warm with the crush of Christmas shoppers. We’d press past the colorful decorations and take the escalators to the fifth floor toy department where Santa held sway. There I took my place at the end of a long line of children, which snaked through an elaborate wooden maze. Each of us, with our dreams tucked up in imaginary lists ready to be unrolled before the great man, stood patiently waiting for our turn. Once on his lap, I became a wooly-mouthed boy. With my memory slipping away, I’d almost forget to tell him I had been good the past year, before stumbling on about wanting some new trains. Not being particularly consumer-oriented, I’d fail to reel off manufacturer and model number, and my vagueness in giving him any precise details (while all the while assuming him to be omniscient, which he wasn’t) meant I never received the trains!

Back at my father’s side, we went to the toy department. In those days, Lionel and American Flyer created elaborate train displays for department stores, even designing the train sales area replete with animated point-of-sales posters. Ranks of tinplate trains sat on stepped displays designed in the best Empire State Building-Art Deco manner, while others would race about the display. Nearby, large tables had been made to demonstrate the best and most exciting trains and accessories. The tables hummed with running equipment and the noise of logs being unloaded, of tiny motors activating machinery to lift them and dump them again onto other cars; of the clatter of tiny coal being ceremoniously dumped into bins, and then being lifted into coal elevators, and reloaded into other cars. Unless a child was particularly aggressive to push past the crush of adult men at the table’s edge, it was near impossible to approach them to see the activity we children could only hear. When I was too old to see Santa any more, these tables still held my fascination.

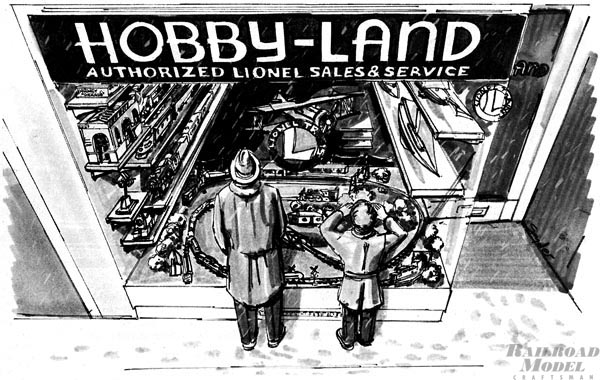

It was at that point that my father decided to expand our itinerary, and we started off downtown. At 25 Park Row, the old turn-of-the-century newspaper center of Manhattan south of City Hall, was Hobbyland, now long since gone. Hobbyland was a deep, narrow store with large glass windows which allowed a generous look into the tinplate-crammed store. While they sold new trains, it was also a museum of the old. Shelves upon shelves sat with old tinplate at prices that would make today’s collectors’ hands shake and set them salivating at the ridiculously low prices. As late as 1947, one could see all sorts of “antique” tinplate, from all manufacturers, including Lionel, American Flyer, Ives, Bing, Marx. You name it, they carried it. Collecting then was not an organized hobby as it is today, and pieces could be bought for a few dollars. Today’s collector would pay for them with cashed stocks and bonds. To my childish eyes, their colors were dull, and they were stamped; many were chipped and they didn’t have the attention paid to prototype detail that the scale trains had. I wanted to see the newest things!

Madison Hardware on East 23rd Street was the next stop. This was another narrow, deep store, piled to the ceiling with shelving full of train equipment. Here too was a mix of old and new, along with building kits, car kits, and piles of old magazines which we would browse through. I questioned the price of a Hiawatha locomotive and tender reposing on a high shelf near the ceiling, and was told it was $75. I was scandalized to think someone would pay that sort of money for an old train! Today’s ads for the same model almost always say, “Ask us for our price!” Today, with all that many more years of tinplate production, Madison Hardware is a collector’s serendipitous delight.

The Gilbert Hall Of Science was our next stop. It sat alone small triangle of land where Fifth Avenue and Broadway crossed at 25th Street. Its round owl-eyed windows were filled with American Flyer trains and magic sets, and jammed outside were children and parents jockeying to get in position to see what was going on inside the crowded showroom. If one were to pass that building today, it’s possible to see the outlines of the old round windows which have been blinded with concrete, and the large Fifth Avenue window filled with ornamental Christmas trees, ironically the product of the company now occupying the site, where once a landscaped layout of American Flyer trains mesmerized passersby.

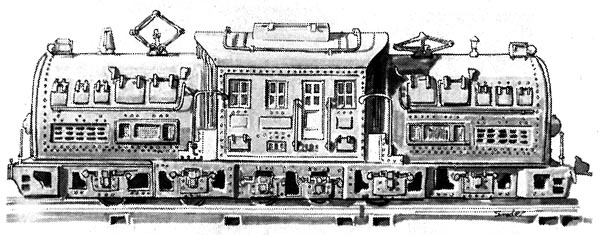

The old showroom was small, and perhaps because of its size, was always crowded with children. There in their resplendent glory were all the cataloged items; my beloved B&O Royal Blue pulling its consist of blue coaches, and the Union Pacific hauling long freights or heavyweight passenger trains. A cutaway Hudson behind glass could be activated at the touch of a button to demonstrate the superiority of worm gearing. One thing American Flyer had going for it; they may have had shiny journals on their trucks, and funny looking couplers, but the locomotives and the cars were scale detailed, and they looked real. How many dreams, besides my own, were born here amongst these happy, noisy young visitors?

After leaving the cacophonous showroom behind, we turned along to 15 East 26th Street, entering an office building on the north side of Madison Square Park and climbed several flights of stairs, rather than wait for the ornate gilded elevators. At the correct floor, we entered the dimly-lit lobby of the Lionel headquarters. There, confronting us in its majesty, was a large wooden mock-up of the Pennsylvania Railroad steam turbine locomotive front, its headlight glowing in the litten atmosphere. To the left of it was a glass window in the wall, behind which sat the receptionist, and who, if asked politely, would dispense a new Lionel catalog. With that in hand, we entered the museum display area containing many of the old Lionel pieces, preserved as a heritage of the company whose name was synonymous with boys and trains.

As many times as I was to visit that showroom, I always spent time examining the models there, perhaps really the seat of my own interest in old timplate. There were trains ranging from the early production of Wide Gauge items, like the old B&O No. 5 tunnel loco, and Standard Gauge pre-1920’s electric and steam models, as well as the more colorful late Standard models, to that herniating leviathan of a Super 381 which defied any child to lift it onto the rails, let alone an adult! There were streamliner sets of all colors, from the yellow and brown Union Pacifics in several sizes, to the silvered New Haven Flying Yankee, to the Milwaukee Road Hiawatha in its orange, gray and black livery: Mickey and Minnie Mouse stood poised on their handcar, ready to race around the track to save the Lionel Corporation from Depression insolvency.

Then there was that most magnificent and hence unobtainable 700E Hudson, sitting in its scale glory on its walnut, brass-plaqued base, with its OO gauge counterpart nearby, a direct contrast with the larger train and in a way a foretaste of what the hobby was to eventually turn to, even though 00 was not the exact scale to be settled upon for “serious railroading.” But who was to know that than? Standing there with my father, surrounded by all these old trains, I felt a continuity with him and the trains he had played with when he was a boy.

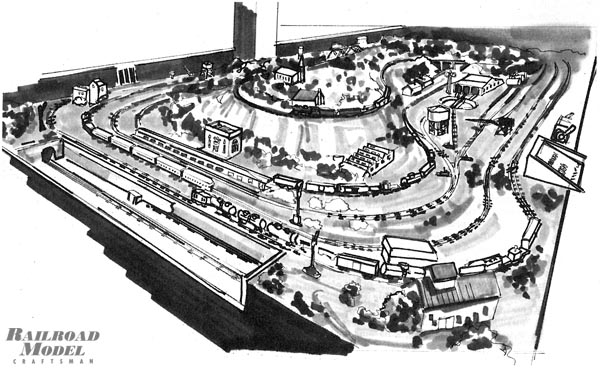

The main showroom was beyond, filled with noisy, excited children and their parents. During the war, Lionel had a large center island layout with a grand reproduction of Niagara Falls facing the entering visitors. Several other smaller tables demonstrated differing train ideas, but it was the main center layout that was most gripping. There, on O-72 multi-tracked mainlines, ran trainsets to stir the weakest father to contemplate bankrupting the family budget to satisfy the train hunger of his young children. By 1949, perhaps reflecting the modernized and expanding postwar train line, Lionel announced a new layout on their center island, and when I saw it, I was not disappointed.

There with all the newest sets, sat a magnificently planned and acessorized landscaped layout. Main lines hummed with freights and passenger trains, activating crossing gates, causing guards to rush out their shacks and warn motorists, and to set warning lights blinking. A GG-1 pulled a string of “Irvingtons” down into a subway tunnel to stop at a station, and then depart again underground, to emerge at another point on the layout. The buildings reflected many of the articles found in The Model Builder, Lionel’s own hobby magazine, and many structures conceived by Frank Ellison and built by the Lionel staff found their way onto the layout.

Want to learn more about old model trains? Purchase your copy of American O Scale by Keith Wills!

Want to learn more about old model trains? Purchase your copy of American O Scale by Keith Wills!

What ran with such grand animation on the layout sat stationary on shelving set into the ways, each set carefully displayed for public inspection. On the opposite wall, in glassed display cases, sat many of the accessories Lionel had made in past years; the power station in its imposing grandeur; the multicolored landscaped bungalows on single grassy bases and in multiple neighborhoods, with their unfurled flags awaiting a breeze; the large Lionel stop station on its landscaped platform; the impressive Hell Gate Bridge, and nearby, a case with steam switchers in four- and six-wheel configurations.

This was truly heaven on earth, and had my father wanted to abandon me in this wonderful place, I wouldn’t have argued, this being the sum total of all my childhood fantasies focused on this one magnificent showroom.

But for all the joy of Macy’s, the hobby shops and the showrooms, it was still necessary to satisfy the inner hunger as well, which meant lunch at a local Horn & Hardat Automat, a sort of mechanical fast food cafeteria chain in Manhattan. There, armed with a fistful of nickels which cashiers threw at you across their polished marble counters when you changed bills, you went to small glass doors set in the wall, behind which sat a variety of foods awaiting nickels to be dropped in slots and knobs turned before the doors would open. To this day I still have a fondness in my memory for their lemon meringue pie and hot chocolate which arrived into your waiting cup from an ornate spout after an equally ornate silvered crank was turned. For a child from the suburbs, this was the height of big city sophistication.

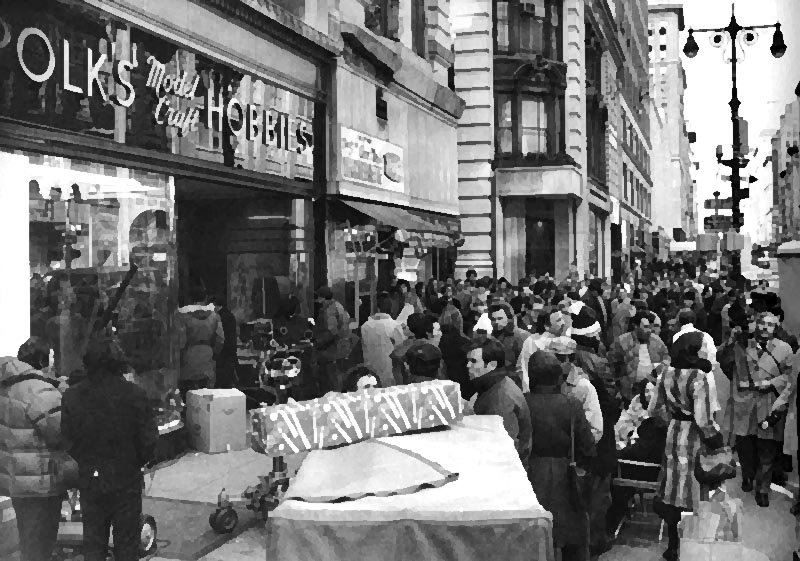

Polk’s Hobby Shop was next. This department store of hobbies contained a different one on each floor. Again, eschewing the slow, tiny elevator, we walked up. On the train floor were several small operating layout tables, and it was there I became aware of Trix Twin, the small, three-rail HO English trains. I was not impressed, having seen better HO downtown at the Gilbert showroom and what abounded on the scale HO layouts around it at Polk’s. There was a collection of custom-built brass O scale locos too, which intrigued me, but they didn’t deter me from my tinplate aspirations. Polk’s was never as crowded as some of the other places, catering as it did to scale modelers, which made it possible to browse around and make purchases without the crush of people driving you out of the store.

Our last stop was Carmen Webster’s, a basement hobby shop on West 45th Street. Her street level window was full of equipment familiar and unfamiliar. There were Lionel and American Flyer, as to be expected, but there were names like Trix Twin (again!) and Varney, Mantua, Lobough, Skyline, and Redball, and magazines to attract the buyer, HO Monthly, The Model Craftsman (later RMC), Trains, and Model Railroader. There was a 1666 Lionel Loco and Pennsy metal caboose on a circle of track on a turntable going flat out in one direction, while the turntable matched its speed in the other direction, rendering the loco stationary but going in full animation. On a lower level, she repeated this effect with a Varney HO Dockside and bobber caboose on a smaller turntable.

In the store below was a world of tinplate and scale railroading. Besides the stock of Lionel and an operating American Flyer layout, shelves were crammed to the ceiling with O scale passenger cars of what seemed an inordinate length compared to my tinplate, and car kits, and Max Gray brass locomotives at prices I thought astronomical.

Perhaps what set Carmen Webster’s apart from the other hobby shops we visited was that this was a comfortable world, where men were making leisurely purchases without the noise and hub-bub of jostling children. This was an adult world where adults fulfilled their fantasies. This was where and when I began to awaken to a world of railroading beyond tinplate, to ideas and standards beyond toy trains. Trains were still magic, but the magic was maturing as I grew.

Perhaps what set Carmen Webster’s apart from the other hobby shops we visited was that this was a comfortable world, where men were making leisurely purchases without the noise and hub-bub of jostling children. This was an adult world where adults fulfilled their fantasies. This was where and when I began to awaken to a world of railroading beyond tinplate, to ideas and standards beyond toy trains. Trains were still magic, but the magic was maturing as I grew.

During the ride home, my father and I examined in the minutest detail any and all of the catalogs and magazines picked up along the way, ignoring the lights rushing by, as they glowed in the early winter evening sky outside our train window. All of the information was stored in my head. It was impossible to ask my parents for all the things I wanted so dearly, as they couldn’t afford my expensive tastes. I sustained my dreams, balancing the affordable and the unobtainable, always alive to what the future might bring.

Those were special days, filled with the spirit of Christmas, accentuated by the prototype trains, the bustling crowds in Manhattan, the fantasy inspiring showrooms and hobby shops, and most of all, the joy my father had in taking me, and our sharing of that closeness that father and son can have sharing the same love of trains.