by Otto M. Vondrak/photos by W. Allen McClelland except as noted

by Otto M. Vondrak/photos by W. Allen McClelland except as noted

“If the Virginian & Ohio has a philosophical basis, I suspect it’s steeped in my own personal conviction that railfanning and model railroading go hand in hand. In order to create a realistic miniature railroad, one must understand the prototype.” So began W. Allen McClelland’s own description of his pioneering HO scale model railroad that introduced us to so many concepts still adopted by hobbyists today.

Allen, in turn, was influenced by Frank Ellison, whose pioneering O scale Delta Lines helped advance the hobby from beyond pure modelmaking toward a purpose of emulating the elements of prototype railroad operation. Ellison wrote, “the art of model railroading consists of condensing everything to within reasonable proportion, with no elements dominating over the others.” Allen certainly took this advice to heart as he set about designing his own model railroad empire.

This Appalachian coal hauler stretching from Ohio through the mountains of Virginia has long been a fan favorite. Of course, you would be forgiven if you mistook the V&O to be a subject for our sister publication Railfan & Railroad (in fact, former R&R editor Jim Boyd photographed and published a few articles about the V&O from the “railfan” perspective in RMC over the years). The truth of the matter is, Allen set the bar and introduced numerous concepts in model railroading that we simply take for granted today. This is probably why more than 60 years after the “golden spike” was driven — and nearly 15 since it became a “fallen flag” — the V&O remains as relevant and inspiring to model railroaders as ever.

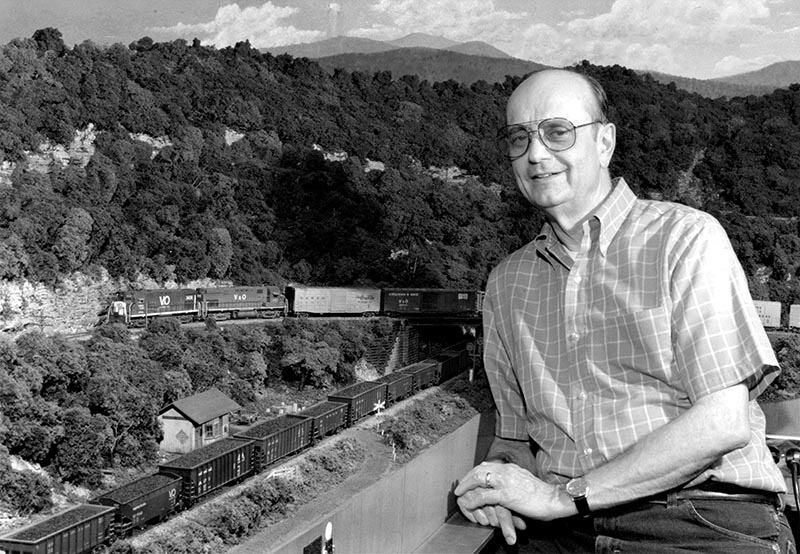

ABOVE: W. Allen McClelland stands in front of the Dawson Springs scene in the late 1980s. At the time, the V&O and many other Dayton-area layouts were referred to as the “Lichen Belt” for their liberal use of dyed lichen to simulate the lush, rolling hillsides of the East.

A Railroad is Born

Allen McClelland was a life-long model railroader who got his start with a two-rail S gauge American Flyer train set in 1946. Looking to economize on space, and also take advantage of the growing number of items available, he switched to HO in 1950. Mountain railroading captured his imagination, with its rolling green vistas, heavy grades with helper districts, and coal traffic as the driving economic force. A series of small layouts culminated in the Miami Valley Railroad (named for the region around his home town of Dayton, Ohio). This 12×16 iteration of Appalachian railroading had all the hallmarks of model railroads at the time, including a “yard” for “switching,” a passenger station, and a main line that looped over itself through a mountain pass to help extend the run (and gain elevation). A switchback to a coal mine provided the main source of traffic. While it was fun to build, it was a closed system that lacked the desired elements of realistic operation. Operations were sporadic after Allen married in 1957 and moved to a new home across town. The Miami Valley was “abandoned” and torn up in 1961, but better things were on the horizon.

While planning his next layout, Allen knew he wanted it set in the mountains. There were already influential model railroads set in the mountainous West like John Allen’s Gorre & Daphetid and Whit Tower’s Alturas & Lone Pine, but Allen was enamored by the lush Appalachians of the East. Further inspired by numerous visits to the region, the advantages became clear. Because the railroads followed narrow river valleys, towns were often small and crowded against the tracks, meaning fewer structures to model. The mountains form a natural backdrop for the layout that could be easily scenicked with dyed lichen representing the lush treetops. Steep grades meant slow trains snaking through the scenery as they gained elevation, helping add to the enjoyment of operating. Modeling coal trains in the late steam era meant short twin-bay hoppers would be the norm, with strings of shorter cars giving the impression of longer trains.

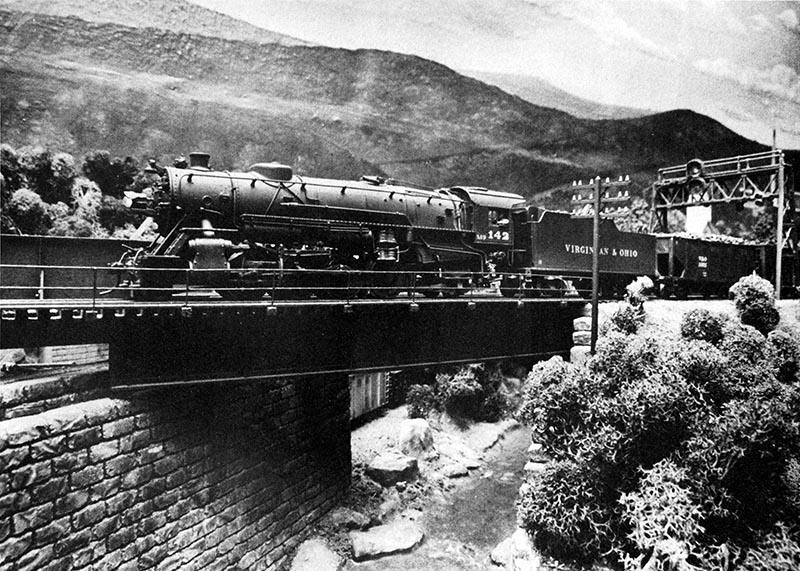

ABOVE: V&O Mikado 142 leads Train EXT-2, eastbound loaded coal train bound for Newport News. The Mike is on the bridge that separates Blackstone and Afton. The steam era on the V&O came to an end on August 26, 1958, but in reality it was December 26, 1980, when Allen decided to move his modeling era forward. —William R. Benysh photo, Brad McClelland collection

State of the Art

Let’s take a step back and look at the state of the hobby in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The majority of scale equipment available came in the form of kits made up of cardstock, stripwood, stamped metal and castings (trucks and couplers sold separately). It took a considerable amount of time and skill to assemble even the most basic kits into a credible model. While you could achieve great results, those who had time invested in building models often were not thinking about how they would be operated, or even of a layout to run them on. Early brass imports were hit or miss, and priced beyond what the average modeler could afford, and the few mass-market locomotives available had deep flanges and crude details. Power supplies were crude, and multi-cab DC block control was only for the most die-hard.

Through the mid-1950s, injection-molded plastic kits began to make inroads into the hobby, and the effect was immediately polarizing. Veteran modelers were dismayed at the “lack of skill” needed to assemble this new breed of kits with one-piece bodies and molded-on details. What they failed to recognize was how accessible these kits suddenly made the hobby, allowing you to quickly build up a large fleet of cars and engines. The same went for plastic structures, offering a viable third option beyond cardstock and stripwood that could be built up quickly and easily.

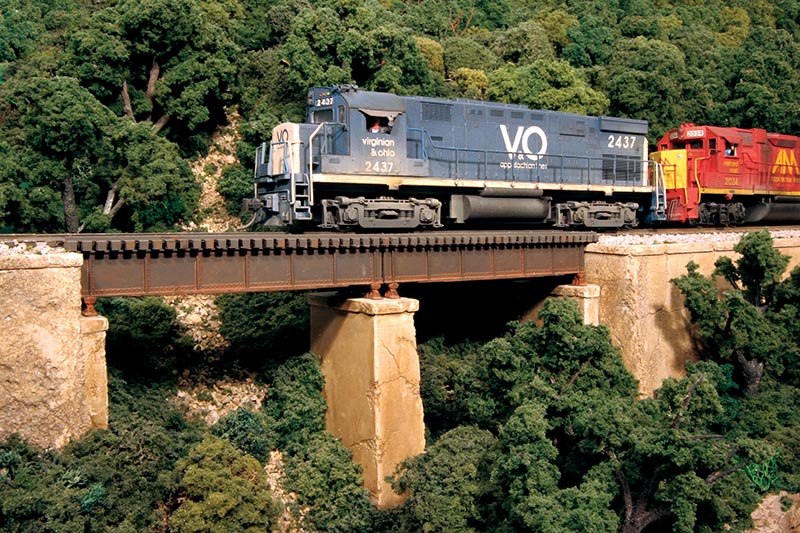

ABOVE: A mix of V&O and AM power help keep priority train Train 261, the Florida Perishable, on schedule. This location is just east of State Line Tunnel on the Gauley Subdivision. —Stephen Priest photo

These advances freed up the average modeler to start thinking about building up a model railroad that more resembled the real thing rather than a simple oval of track on the living room floor. However, no one was thinking about adding a track that ran off the edge of the layout, or perhaps snuck behind a backdrop to represent distant terminals or interchanges with other roads.

The other constraint at the time was electronics. Even larger model railroads were based on overlapping loops and dogbones that were operated from a central control panel. Designed for solo operation, the skilled operator could even get a second or third train running with careful manipulation of switches turning on and off various electrical blocks. Such operations were fun to watch and challenging to orchestrate, but did little to encourage prototype operation. Around-the-walls designs with peninsulas simply did not exist.

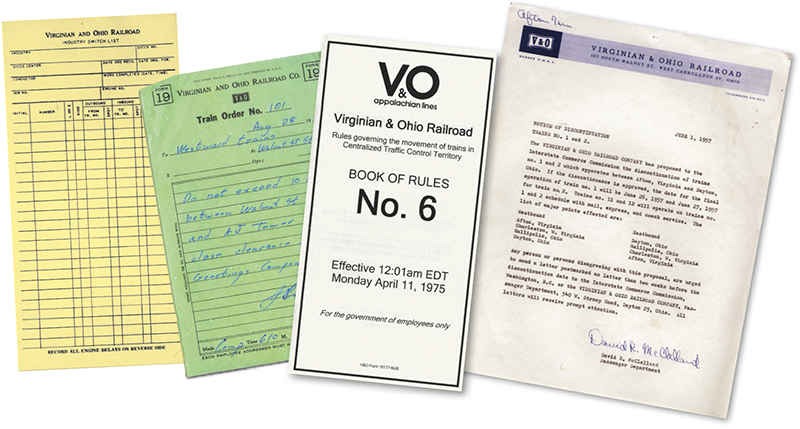

ABOVE: Examples of paperwork from the V&O include a switch list, train order (printed on tissue paper), an employee rulebook, and a notice announcing the discontinuance of Trains 1 and 2 (the Midstates Limited through service between Washington, D.C., and St. Louis) in 1957. Besides adding to the illusion of reality, they also serve a purpose in the practical operation of the railroad.

Allen knew from the start that his next railroad would feature a linear design, even though walk-around controls did not exist as we know them today. Still, the answer was obvious if he was going to build a railroad that behaved like the real thing, and so he forged ahead. General Electric seemingly answered the call when they introduced their ASTRAC (Automatic Simultaneous Train Control) analog command control system in 1963. Using RF frequencies that communicated with onboard receivers, you could control up to five trains at once on the same track. Allen hacked this system and quickly adapted it for the type of walkaround control he needed so operators could follow their trains across the system.

Beyond the Basement

And what of this system? As scale model railroading entered the 1960s, most hobbyists chose “cutesy” names for their railroads, no doubt thought up as they sat at their master control panel wearing their hickory-stripe hat and smoking a pipe. Allen knew right away he wanted a portion of his railroad rooted in his home state of Ohio. Having Ohio in the name also alluded to his interests in both the Baltimore & Ohio and Chesapeake & Ohio railroads. It was decided his old Miami Valley Railroad would be the predecessor of the new railroad, representing the western end. The eastern Appalachian route crossing West Virginia and Virginia was consolidated into the pleasing Virginian. Thus the “Virginian & Ohio” was born, with its “coonskin” logo adapted from the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway…