Introduction

Introduction

by George Riley and Otto M. Vondrak/photos as noted

Have you ever stood by a busy main line to watch the parade of evening commuter trains as they flash by with their colorful consists? Does the idea of adding a new dimension of operations to your model railroad interest you? Are you up for the challenge of modeling unique equipment and infrastructure? Then we invite you to consider the commuter. These specialized trains run in many configurations, from a single car on a once-a-day schedule to 10-car trains departing every half-hour. Whether you have an established model railroad or are just starting out; whether you model the steam era or modern diesels; whether you model the New Mexico desert or a bustling East Coast city, you can make commuter trains a part of your plans.

All Aboard

Bankers’ Special… Clockers… Dinky… Plug… Scoot… They all go by different names, but commuter trains as we know them can trace their origins to the 1840s, when the first railroads built north from New York City into the undeveloped countryside. The reliable and inexpensive transportation provided by the railroad allowed more people to relocate to the country and use the train to travel back and forth to their job in the city each day. As a result, railroads offered a reduced or “commuted” fare to those purchasing multiple trips in advance, and the “Commuter” was born.

Depending on the population, suburban routes could extend anywhere from 25 to 75 miles away from a city. Local commuter trains typically stopped at every station along the way, while express trains offered faster service between major points with fewer stops. Depending on the route and population density, some trains operated only one roundtrip a day, while others scheduled multiple runs with increased service during the morning and evening “rush hours.” Getting away from the major cities, commuter trains of a different type could be found on lines where a major employer like a coal mine might warrant the operation of a single train to bring workers in and out from nearby towns each day. As late as 1959, a single Budd Rail Diesel Car was used as a school bus service to shuttle students in a remote portion of West Virginia coal country served by the New York Central.

Afternoon trains meet at bucolic East View, New York, on the New York Central Putnam Division in the late 1940s. Because the majority of the line was single track, meets had to be planned at sidings along the way. — Frank Schlegel photo, Glenn Rowe collection

Because of their frequent schedules and connections from suburb to city, many trains carried milk, mail, and express shipments, which helped offset the cost of operation. While commuter trains were originally operated on a profit basis, competition from improved highways and automobiles coupled with the effects of the Great Depression put many railroad operations in the red by the 1930s. In the postwar era, commuter services were abandoned in some smaller cities as factories shut down and not enough people rode the trains to make them profitable. By the 1960s and 1970s, many metropolitan areas had set up public transit authorities to fund and operate the remaining services, ending an era of privately operated passenger trains. As the public’s attitude toward mass transportation changed and suburbs continued to grow, many new commuter services were launched starting in the 1990s and continuing through to the present day.

Unique Equipment for All Eras

If your idea of a commuter train is a featureless silver tube of lookalike cars, think again. The earliest commuter trains were simple day coaches hauled by steam engines. It was also common for these trains to haul bags of pre-sorted mail, morning edition newspapers, and express parcel shipments in a baggage car. A dedicated Railway Post Office car might also be found on some runs to pick up and sort mail along the way. Milk traffic was also very common in the Eastern cities. Farmers would meet the early morning train with metal canisters full of fresh milk which would be loaded into special refrigerator cars outfitted for passenger train operation. The milk would be delivered to a city creamery for processing, and the empty canisters would be returned to the farmer in the evening. Depending on the length of the run, a club car or parlor car might be part of the consist, where commuters could enjoy a plush seat and potent drinks to help them relax on their ride home from work.

Where ridership did not justify operating a full locomotive-hauled consist, a single self-propelled car might be used instead. Gas-electric “doodlebugs” were common on many low-density branchlines from 1910 until the 1940s. For some roads, a single doodlebug run represented the company’s entire passenger service offering. Manufacturers such as Brill and Electro-Motive Corporation produced self-propelled units based on heavyweight passenger car designs through the 1920s, but many of these early efforts were often prone to breakdowns and were unpopular with the riding public due to the exhaust odors that would seep into the passenger compartment. When warranted, a doodlebug might tow an unpowered trailer or coach to add extra passenger capacity. While the Great Depression eroded ridership and made a strong case for using doodlebugs, the unexpected surge of traffic during World War II sidelined many of these units and forced the railroads to return to running conventional trains to meet demand.

Self-propelled diesel technology born 50 years apart meets at Tigard, Oregon, on June 22, 2017. Portland’s TriMet uses the classic Budd Rail Diesel Cars to fill in during rush hour; otherwise, runs are covered by the more modern Colorado DMU cars. — Otto M. Vondrak photo

Budd’s streamlined stainless steel Rail Diesel Car was introduced in 1949 and quickly found many customers across the country looking to modernize their secondary services while reducing operating costs. The traveling public welcomed these efficient diesel-powered units outfitted with the latest advancements in passenger comfort, including air conditioning and fluorescent lighting. Where it was justified, two or more RDCs could be coupled together to meet ridership demands — all controlled by a single engineer. Boston & Maine owned the largest collection of RDCs, using 86 cars to replace its fleet of conventional passenger trains by the end of the 1960s.

The Budd RDC was available in several configurations, including coach, combine, and Railway Post Office. Some railroads outfitted their cars with snack bar service to provide riders refreshments on some of the longer commuter routes.

At the turn of the last century, some larger municipalities passed ordinances against steam operation inside the city limits to curb pollution, which forced some railroads to electrify their commuter zones. A fierce battle to promote the emerging technology to the railroads ensued, with General Electric pushing for direct current propulsion while Westinghouse advocated for alternating current. Some railroads like Lackawanna, Reading, and Illinois Central chose to rely entirely on electric “multiple-unit” (m.u.) cars for these upgraded services. These self-propelled trains could be of any length, all controlled by a single operator. Other lines like Canadian National, Long Island Rail Road, New Haven, New York Central, and Pennsylvania Railroad ran a mix of electric m.u. and locomotive-hauled trains.

Gulf, Mobile & Ohio EMD F3A No. 880B leads the weekday commuter train from Chicago Union Station to Joliet, Illinois, in July 1978. GM&O had merged with Illinois Central in 1972, yet the classic equipment remained unchanged until replaced in 1978. The F3 would enjoy a longer career, rebuilt for service in Boston and later New York before it was retired in 2008. — Chuck Zeiler photo

Commuter trains of the 1950s were often rolling museums with equipment dating back to the first World War. Because of the utilitarian nature of the commuter train and the lack of funding to invest in new equipment, many of these older-style trains remained in service well beyond their expected lifespans. It was not uncommon to find 1920s steamheated heavyweight coaches in service well into the 1970s and 1980s. While railfans delighted in the vintage equipment, riders expressed their frustration at having to ride in decrepit antiques. As railroads quickly converted to new diesel locomotives in the postwar era, secondary services were often the last bastion of steam power. In fact, Grand Trunk Western’s commuter service between Detroit and Pontiac, Michigan, was steam-powered until 1960. Across the country, stations and equipment fell into disrepair, and service began to suffer as railroads entered a period of decline nationwide. Some railroads tried to discourage ridership by closing stations and making timetables unavailable to the public.

When the federal government formed Amtrak in 1971 to alleviate the nation’s railroads from the responsibility of operating long-distance passenger services, the burden of operating commuter trains remained. Surplus equipment originally built for the famous streamliners of the 1940s allowed some lines to mercifully retire some of the oldest cars assigned to suburban service. Some railroads continued the tradition of operating “bar cars” where light refreshments and drinks were made available. Diesel power ranged from locomotives built specifically for passenger service (such as steam-generator-equipped EMD cab units, or Alco road switchers), to second-hand freight locomotives rebuilt with modern head-end power (HEP) generators. When it came time to upgrade electric operations, the only modern options available were designs from manufacturers in Europe or Japan.

The Next Station Will Be…

Stations come in all styles, from expansive Art Deco multi-track terminals to a simple strip of asphalt supporting a repurposed bus shelter. Some stations are modern structures built of glass and steel, while others are older buildings restored and updated for today’s needs. Some have high-level platforms to facilitate faster passenger loading, while others retain their ground-level facilities to save construction costs. Some use elevators and overpasses to safely move passengers from one side of the tracks to another. In multi-track territory, platforms are either located alongside each track or built between tracks in an “island” configuration. The choice is up to you as to what represents your needs and available space. In the most extreme situations, even a grade crossing can be used as a station stop.

Ken Miller models the Pittsburgh PATrain, including the compact former Baltimore & Ohio Grant Street Station, on his HO scale model railroad representing Chessie System between Pittsburgh, Pa., and Cumberland, Md., in the late 1980s. The real PATrain was cancelled in 1989, and the equipment was purchased and moved to Connecticut in 1990. — Ken Miller photo

One misconception is that station platforms need to be as long as your longest train. On the average HO-scale model railroad, a three-car passenger train is almost four feet long, and making a station facility to match would eat up precious real estate (as in real life). Except at the largest terminals, it is common for platform areas to be only one or two cars long, with passengers directed where to disembark prior to arrival.

Operational Potential

Many modelers shun passenger operations altogether, either because they lack the space or the operations are perceived as a boring “ping-pong” schedule between two terminals. The truth of the matter is, you control how much space you want to dedicate and how extensive you want the operation to be.

Most passenger cars are nearly twice as long as a standard steam era freight car, which means even the shortest commuter trains can start to take up a lot of valuable track space. If you are thinking about adding commuter service to your model railroad, you’ll have to consider the following: Will your trains be stored and serviced in a yard, or run off the layout to staging? How many stations will you represent? Will your trains have any scheduled layover, or duck into sidings and yards when not in use? Can you use existing stations or squeeze in new ones? What about parking lots? Just remember, not every facility and detail needs to be modeled for a successful and convincing operation.

When it comes to operations, consider the fact that your commuter trains are First Class by rulebook, which means they have priority over all other traffic on your line, including freight trains. For example, you could operate a commuter shuttle every two hours over your line, forcing your freights into sidings and keeping crews on their toes as they dodge the “dinky.” Don’t have room for a locomotive-hauled train? A single RDC or gas-electric doodlebug is all you need to introduce the most basic services to your line without investing in a lot of extra equipment. Don’t be afraid to start small. Like the real thing, you can always acquire more equipment to meet future service demands.

While it’s true that many trains operate on a back-and-forth schedule that cycles between two terminals, commuter train operation can be much more involved than that. For instance, a route 50 or more miles long may be split up into multiple service zones, utilizing different equipment and operating patterns. One example is Metro-North Railroad’s Harlem Line, which extends 82 miles from Grand Central Terminal to Wassaic, New York. When I was growing up, service on this former New York Central route extended only as far as Dover Plains, 77 miles from New York City. Electric trains operated on the lower Harlem Line between New York and North White Plains. Diesel trains provided service between North White Plains and Brewster. In the old days, electric locomotives would haul trains to North White Plains and then switched out with a steam or diesel engine to continue the trip north. After the Penn Central merger, former New Haven dual-mode EMD FL9s (which could draw power off the NYC third rail or run off its own diesel) eliminated the need for the engine change. Budd RDCs ran in a shuttle service on the rural single- track line between Brewster and Dover Plains. Added to the mix was a Conrail local freight that worked industries along the way, including produce and grocery warehouses, lumber yards, fuel oil dealers, a coal-fired power plant, and a feed mill.

Launched in 2009, MetroTransit’s Northstar commuter rail serves a 40-mile corridor between Minneapolis and Big Lake, Minnesota. Locomotives are MP36PH-3Cs built by MPI, while Bombardier built the bi-level coaches. The trains run in push-pull service, with the last coach containing cab controls. — Lou Gerard photo

Of course, you don’t need to model the suburbs of New York to justify operating commuter trains. Many new commuter rail operations have been established in regions with no previous history of suburban service. The New Mexico Rail Runner Express connects the metropolitan areas of Belen, Albuquerque, and Santa Fe, on a mix of existing and newly constructed track opened in 2006. Opened in 2009, the Metro Transit Northstar Commuter Rail Line connects Minneapolis with the northwestern suburbs running on a portion of former Great Northern track now operated by BNSF Railway. Using a fleet of second-hand Amtrak F40s and former Metra bi-level coaches, Music City Star provides service between Nashville and Lebanon, Tennessee. The 32-mile line, opened in 2006, is operated by shortline Nashville & Eastern for the Tennessee Regional Transportation Authority.

Some cities attempted to subsidize their commuter trains but eventually discontinued these services for a variety of reasons. In 1975, the Port Authority of Allegheny County assumed responsibility for the commuter service between Pittsburgh and Versailles, Pennsylvania, operated by Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. As in Detroit, refurbished equipment and improved service could not stem the tide of diminishing ridership due to a general economic downturn thanks to the closure of area steel mills, and service was canceled in 1989. All was not lost — the trains were purchased by the Connecticut Department of Transportation for the start-up of its new “Shore Line East” service between New Haven and New London, Connecticut, in 1990.

Consider the Commuter

Commuter trains historically provided a challenge to some modelers looking to add accurate consists to their operations. While some railroads used conventional equipment that was readily available in model form, others employed unique designs that were previously only available as expensive brass imports or obscure craftsman releases in resin. As manufacturing processes have become more streamlined in recent years, we are starting to see new releases of commuter train models in ready-to-run formats. What isn’t being mass-produced is sometimes made available for hobbyists using advanced 3-D printing techniques. If you’re considering developing a free-lanced system, consider paging through the catalogs of some of the overseas manufacturers — many off the- shelf designs from Europe and Japan often find their way onto American systems with few modifications. The possibilities are endless.

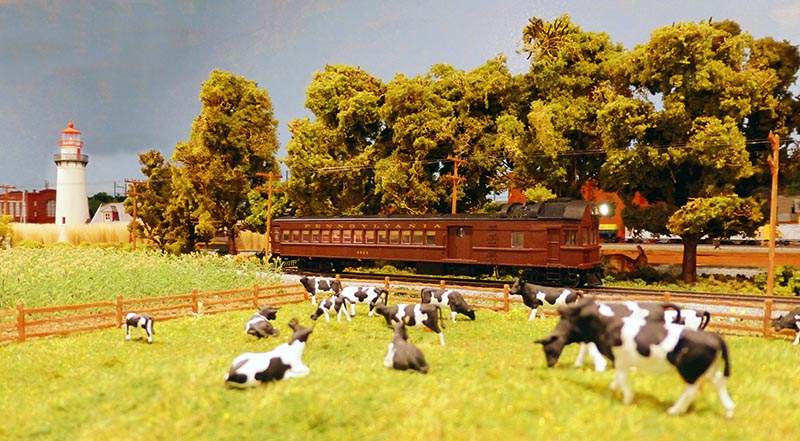

Commuter trains can be as basic as this Pennsylvania Railroad gas-electric car rolling through the rural farmlands on David Sheppard’s HO-scale layout. No. 4644 is a heavily modified HO-scale Bachmann gas-electric doodlebug model. — David Sheppard photo

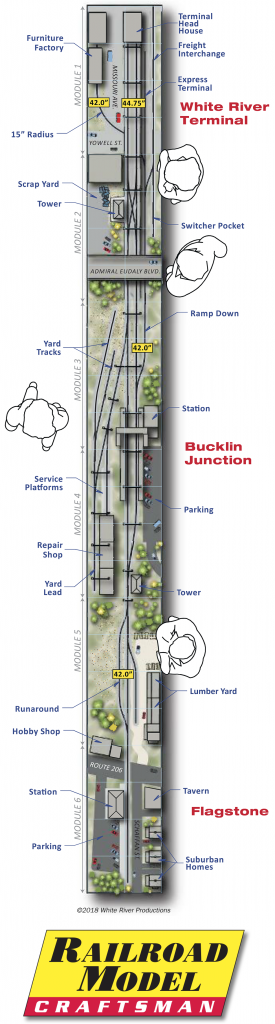

We invite you to follow along as we construct a series of modules to represent a basic commuter train operation. Inspired by the new release of modern NJ Transit commuter train models by Atlas Model Railroad Co., our HO-scale model railroad is a freelanced concept that includes design elements from different locales across the country. The entire layout consists of six four-foot modules. We chose this size for its ease of construction, not to mention storage and transport. The main line, set up end-to-end, measures 24 feet. You might want to consider the addition of curved sections to add visual interest and fit your available space. You can adapt any of these module plans into your existing layout, expand them, or use them as-is. While the track plan is designed using common No. 4 and No. 6 turnouts and Code 83 track components, we encourage you to modify this plan any way you see fit.

NJ Transit was established by the New Jersey Department of Transportation in 1979 to coordinate all statewide bus and rail transit services among the private operators at the time. In 1983, NJT assumed direct responsibility for the operation of the trains as Conrail exited the passenger business. At the time, the commuter rail system represented a disparate collection of vintage rail equipment, including 1920s electric m.u. cars inherited from the Lackawanna, 1930s ex-Pennsylvania Railroad GG1 electric locomotives, 1940s lightweight coaches purchased second-hand from Santa Fe and Burlington Northern, and a handful of 1950s Budd RDCs that once ran on the Jersey Central and the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. The state had previously purchased the newest equipment in the 1970s, including new GE U34CH diesels and Pullman-Standard coaches for Erie Lackawanna and new Budd (later General Electric) “Jersey Arrow” electric m.u. cars for the former Pennsylvania Railroad electric operations. Over the next few years, NJT embarked on a modernization program to increase reliability and expand services where they were needed. New equipment was purchased, stations rebuilt or replaced, and new lines were opened.

Atlas Model Railroad Co. released HO-scale models of Bombardier ALP-45DP dual-mode locomotives and Bombardier multilevel coaches in 2016, which served as the inspiration for our new project layout. The models look right at home on Andy Rubbo’s model railroad, which represents a portion of the old PRR Northeast Corridor main line. — photo courtesy Atlas Model Railroad Co.

Today, NJT operates 11 lines serving 164 stations split into two divisions. The Hoboken Division includes diesel and electric services formerly operated by Erie Railroad and Delaware, Lackawanna & Western out of Hoboken Terminal. The Newark Division services terminate at Newark, New Jersey, and New York Penn Station, and include former Pennsylvania, Jersey Central, and New York & Long Branch diesel and electric services. NJT operates two interstate routes, including the Atlantic City Line between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Atlantic City, New Jersey, and the Main Line/Port Jervis Line, operated in cooperation with Metro- North Railroad between Hoboken, New Jersey, and Port Jervis, New York. While our model railroad draws inspiration from NJT and strives to replicate some of the look and feel, it is not an exact recreation of any particular operation or location.

Our tour begins at White River Terminal, which represents a modest two-level train station serving a small city. You don’t need a scale model of Grand Central Terminal to support passenger operations on your layout, and this “storefront” terminal is a great example. The free-lanced design was inspired by such facilities as the Lackawanna terminal in Buffalo, New York, the North Shore terminal in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the Jersey Central terminal in Newark, New Jersey. Passenger trains arrive and depart from the two tracks on the upper level, while freight and express shipments are handled from the lower level (which in modern times could be used as a warehouse or team track siding). A single track running off the edge of the layout represents the connection to the outside world.

Our tour begins at White River Terminal, which represents a modest two-level train station serving a small city. You don’t need a scale model of Grand Central Terminal to support passenger operations on your layout, and this “storefront” terminal is a great example. The free-lanced design was inspired by such facilities as the Lackawanna terminal in Buffalo, New York, the North Shore terminal in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the Jersey Central terminal in Newark, New Jersey. Passenger trains arrive and depart from the two tracks on the upper level, while freight and express shipments are handled from the lower level (which in modern times could be used as a warehouse or team track siding). A single track running off the edge of the layout represents the connection to the outside world.

Freight interchange can be simulated by adding a cassette to the end of the layout, or by simply adding or removing freight cars by hand from the interchange track. A second freight siding ducks under the main line on tight 15-inch radius curves to serve a furniture factory. The pocket track provides a dedicated place for your freight switcher to park and allows you to model a small engine servicing scene if you choose. The freight would be handled by a connecting carrier, such as Conrail, Norfolk Southern, or shortline Morristown & Erie, depending on your era and personal preferences. The freight track ramps up to connect with the passenger main in the next scene.

A set of double-crossovers right outside the terminal is controlled by an interlocking tower and allows passenger trains to arrive and depart from either track. A scrap yard adds visual interest and detail to a landscape made up of tall urban buildings, while the viaduct carrying Admiral EuDaly Boulevard over the tracks helps further separate the city scene from the rest of the layout.

The next two modules represent a suburban junction called Bucklin Junction. The freight track joins the passenger main just north of the commuter station. A large park-and-ride lot helps support the ridership at this busy station, which features two platforms connected by elevators and a pedestrian overpass. This would be an excellent opportunity to pose some transit buses parked at the drop-off area in the parking lot. Bucklin Junction is also the location for this line’s shop and yard facility. The yard is small, but it will allow for the storage of a modest commuter fleet.

Don’t forget to leave room for cars assigned to maintenance-of-way (MoW) service. This is a good excuse to include various steam-era freight cars on a modern layout, as such equipment would often be pressed into company service years after their useful interchange life had ended. Consider a basic fleet consisting of a flatcar, gondola, dump car, and caboose. Remember that MoW trains can also be an important part of your operating schedule.

If you have the room to expand the length of this module, consider having one of the yard tracks connect back into the main to allow a runaround that will enable you to shuffle consists as needed. Bucklin Junction is envisioned as the midpoint of a busy branchline, where the main line shrinks from two tracks to one and is the end of the electric zone (more on that in future installments). An interlocking tower helps coordinate the movements at the junction, including the connection to the freight line.

Gladstone, New Jersey, is the end of New Jersey Transit’s Gladstone Branch. The line is single-track from Summit to Gladstone, requiring the use of passing sidings to cope with rush-hour traffic. The line is served exclusively by electric m.u. cars like the train seen here on March 30, 2012. The 1891 depot looks like something out of the Atlas Model Railroad catalog, doesn’t it? — Otto M. Vondrak photo

The last two modules represent the end of our single-track line at Flagstone, loosely based on NJ Transit’s branch to Gladstone, New Jersey. A lumber yard and building supply center is located in Flagstone and is served by a single siding alongside the lumber sheds. Route 206 crosses through the middle of town, which includes a hobby shop, a tavern, and a few small homes surrounding the wood-frame passenger depot. The runaround track helps make deliveries to the lumber yard a bit easier, and it gives a place for the local freight to get out of the way of any conflicting passenger movements. The flavor of this scene is definitely rural suburbs, where you’re just as likely to find a farmer’s tractor putt-putting down the road as you would a flashy sports car parked in the commuter lot.

Throughout the series, you will learn techniques such as module construction, structure kitbashing, and creating realistic scenery effects. Our railroad represents a portion of an electrified district, which includes the installation of an overhead catenary system using readily available commercial parts. We’ll also show you how to add signals and control systems using easily adaptable products. Despite the small size of the layout, we’ll demonstrate the potential for a variety of different operating scenarios involving passenger and freight trains. Whether you are a novice or a seasoned veteran, we invite you to settle into your seat as the train is about to pull out of the station… We’ll see you down the line.

George Riley is a life-long model railroader and finescale model builder with a strong interest in electric operations and passenger trains. Currently residing in Lynchburg, Virginia, George also serves as the Marketing Director for White River Productions.

Otto M. Vondrak became hooked on trains after his first ride on the Harlem Line as a toddler. A co-founder of the RIT Model Railroad Club, Otto currently lives in Rochester, New York, and is the associate editor for our sister publication Railfan & Railroad.

This article appeared in the January 2018 issue of Railroad Model Craftsman.

This article appeared in the January 2018 issue of Railroad Model Craftsman.